On our Kickstarter page, we provide a brief summary of our game-in-development–Ulus: Legends of the Nomads, intended to promote and protect the threatened Mongolian culture, language, and script.

On our Kickstarter page, we provide a brief summary of our game-in-development–Ulus: Legends of the Nomads, intended to promote and protect the threatened Mongolian culture, language, and script.

Here you can find more detail about the way in which we have woven Mongolian culture, history and mythology into the game–its characters, its locations, even the way the players move.

After that, you’ll find the rules and gameplay.

As we are still firming up some of the exact mechanics, the final version may differ slightly from what you see here. We may end up with eight gods and eight champions, for example, rather than seven, as eight is an important and propitious number in Mongol culture. But this will give you a good idea of how the game will look, play, and feel, and how it will try to celebrate Mongolian history and culture at a time when, especially in Inner Mongolia, it is under threat.

THE GODS

Ulus: Legends of the Nomads begins with the Mongolian gods–of which there were many, enough to suggest an expansion pack in the future! In our fictional version, the gods all have different and competing visions of the future of the Mongol lands, and, like the Greek gods, they play out their arguments on the human chessboard, and can be remarkably petty and even cruel in playing with their human pawns. Each god (working through the player) chooses a champion who will fight for that god’s vision of the Mongol future and the Mongol soul. NOTE: none of the gods is a god of war, and none of the visions of the Mongol future is of a brutal military empire. That Western stereotype of the Mongols is 800 years old and deserves to be laid to rest.

Each god is associated with sacred sites on the game map, whose importance will be explained in the rules. And in order to achieve their own version of the Mongol future, each god needs their champion to acquire certain assets that will be vital to create and sustain their particular Ulus. Again, the business of acquiring and holding onto sufficient assets will be explained in the rules, as will the act of divine intervention.

Tengri

Tengri, the sky god, was the chief deity worshipped by the ruling class of the Central Asian steppe peoples in 6th to 9th centuries. He was the god who created all things, father of the sun and the moon. Tengri was sometimes personified as a pure, white goose that flies constantly over an endless expanse of water, which represents time. Beneath this water, Ak Ana, the White Mother, calls out to him saying “Create!”

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Tengri wants to establish an ever-expanding empire of manufacturing, commerce, and trade.

Sacred places: Burkhun Khaldun, The Burial Mounds of Noin-Ula

Assets: Eagle, Ger, Camel, Horse, Map, Airag, Khalka Saddle, Bow

Divine intervention: Apocalyptic Lightning

Lobsogoi

Lobsogoi, who appears in the Buryat version of the Geser epic, is a trickster demon, who was born from the backside of the slain Atai Ulan, king of the malicious gods of the East. Think of him as the Mongol equivalent of Loki.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Lobsogoi is the only god who does not have a specific vision of the future of the Mongol lands. His only aim is to make trouble for and thwart the other gods, who see themselves as mightier and superior to him. He is, in a sense, the Mongol equivalent of Loki. His path to winning is to ensure that no other player ends up with the assets and the strength needed to establish the Mongol empire of their vision. As the players do not reveal which god they serve, it is not initially clear who is playing for Lobsogoi, as that player may pretend to be collecting certain assets to give a false impression. In an ideal game, Lobsogoi (as in the game Mafia) would not be identified until the very end. Likewise, Lobsogoi could pretend to be helping other players, only to betray them.

Sacred places: Uureg Lake, Dalad Banner

Assets: As Logsogoi has no intention of creating a Mongol future, his champion can collect whatever assets they please simply to deny them to others, or to mislead other players.

Divine intervention: As Lobsogoi is a trickster and shape-shifter, he can use any of the other gods’ forms of intervention.

Ulgen

Ülgen symbolizes goodness, welfare, abundance of food and water. In addition, he controls the atmospheric events and movements of stars. He creates land for people to live on, the heads of both humans and animals and the rainbow. He was regarded as the patron god of shamans and the source of their knowledge. In Turkic and Mongolian mythology, the birch tree, regarded as a cosmic axis between earth and sky, was regarded as sacred to him, as was the horse.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Ülgen wants to establish an empire of spirituality.

Sacred places: Ulaan Tsugalan, Mogao Caves

Assets: Ovoo, Talisman, Tovshuur, Morin Khuur, Prayer Flags, Sami, Ger, Horse

Divine intervention: Flash Flood

Mergen

Mergen is a deity of abundance and wisdom. He is often depicted as a young man with a helmet and a bow riding on a white horse, with a bow and arrow in one hand. He lives on the seventh floor of sky. Mergen symbolizes intelligence and thought.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Mergen wants to establish an empire of education, scholarship, and learning.

Sacred places: The Sacred Yurts of the Darkhads, Mogao Caves

Assets: Pen and Ink, Paper, Map, Suutei Tsai, Morin Khuur, Tovshuur, Ger, Horse

Divine intervention: Plague of Locusts

Etügen Eke

Etügen Eke (“Mother Earth”), is an Earth goddess who lives in the middle of the Universe, patroness of the Homeland and nature. All living beings are subordinate to her. Traditionally, the dominant role in determining the fate of people and nations belonged to Tengri, but natural forces yielded to Etügen. Sometimes on Tengri’s command, Etügen punished people for their sins, but she was generally considered a benevolent Goddess. To appease the goddess Etügen, sacrifices were made every spring in preparation for the cattle-breeding season and before planting crops. Sacrifices were also conducted near rivers and on the banks of lakes in the autumn, after the completion of the harvest. Etügen is often represented as a beautiful young woman riding a grey bull.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Etügen wants to establish an empire of herding, farming, and nomadic self-sufficiency.

Sacred places: Burial Mounds of Noin-Ula, Dalad Banner

Assets: Camel, Yak, Goat, Sheep, Bankhar Dog, Horse, Ger, Suutei Tsai

Divine intervention: Famine

Umay

Umay is a protector of women and children. Umay is always depicted together with a child. There are only rare exceptions to this. It is believed that when Umay leaves a child for a long time, the child gets ill and shamans are involved to call Umay back. The smiling of a sleeping baby shows Umay is near it and crying means that Umay has left. Umay helps people to obtain more food and goods and gives them luck. As Umay is associated with the sun, she is called Sarı Kız ‘Yellow Maiden’, and yellow is her colour and symbol. She is depicted as having sixty golden tresses that look like the rays of the sun.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Umay wants to effect a reconciliation and union between the gods, and to protect all Mongol people. She is the opposite of Lobsogoi, and one of her principal roles in the game is to identify Lobsogoi, unmask him, and thwart his intentions.

Sacred places: Sacred Yurts of the Darkhads, Burkhun Khaldun

Assets: Bankhar Dog, Prayer Flags, Horse, Map, Ger, Eagle, Airag, Boortsog

Divine intervention: Snowstorm

Burkut

Burkut is the Eagle God. He is often portrayed on top of the Ulukayın (Tree of Earth), and it is said he is the bird with copper talons, whose right wing covers the sun, and whose left covers the moon.

Vision for the Mongol people and their lands: Burkut wants to turn the Mongol lands into a refuge for all wild creatures.

Sacred places: Uureg Lake, Ulaan Tsugalan

Assets: Bankhar Dog, Horse, Eagle, Reindeer, Wolf, Snow Leopard, Camel, Map

Divine intervention: Attack by wolfpack

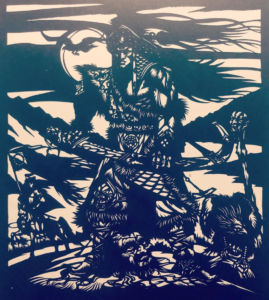

THE CHAMPIONS

Each of the Mongol champions is drawn from history or mythology (though in some cases the line between the two is unclear). The role of the champion is to travel the Mongol lands, to acquire the assets their god wants, and to defend them against natural enemies and rival champions. The guidelines for trading and fighting are explained farther down, in the rules.

Chinggis Khan

Chinggis Khan, whose birth-name was Temüjin Borjigin) was the founder of the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous land empire in history, and is regarded by present-day Mongolians as the founder of Mongolia.

He founded the Empire by uniting several Mongol tribes, at which point he was proclaimed Chinggis Khan, meaning “Universal strong ruler and lord.” He then launched invasions that overran lands from Poland to Korea.

Notwithstanding his brutal conquests, however, he also did much to promote enlightened ideas within his Empire. It was he who made official the Uyghur script as the official writing system of the Empire. He also promoted religious tolerance within the Empire and encouraged and protected trade, thus facilitating cultural growth of areas from Europe to Southeast Asia.

Alun Gua

According to Mongolian tradition, Chinggis Khan was descended from the union of a grey wolf and a white doe. But eleven generations after that union and ten generations before the birth of the great Khan is the semi-mythical figure who marks the transition between the supernatural and the human, the past and the future: Alun Gua, or Alun the Beautiful.

Her first two sons, Begunuitei and Belgnutei, were sired by her warrior-king husband Bodonchor Munkhang. After the king’s death, the story goes, she gave birth to three more sons, which she credited to a glittering divine visitor who entered her ger through its chimney-hole and impregnated her.

This account aroused a certain amount of suspicion, and her two eldest sons accused her of a dalliance with a servant.

In response, she invited them for a meal, gave each of them an arrow, and told them to break it. They did so. She then gave them a bundle of five arrows and challenged them to break it, which they could not.

“If the five of you are divided,” she said, “you can each be easily conquered. Together, though, like the bundle of arrows, nothing can harm you.”

And thus, as they say in the fables, each of her sons thrived and became the ancestor of a different Mongol clan.

Zanabazar

Western popular culture today may depict the Mongols as bloodthirsty brutes, but Zanabazar was nothing of the kind.

Zanabazar was declared spiritual leader of Khalkha Mongols by a convocation of nobles in 1639 when he was just four years old. The Dalai Lama later recognized him as the reincarnation of a famous Buddhist scholar, and bestowed on him the Sanskrit name Jñānavajra meaning “thunderbolt scepter of wisdom.”

In addition to his spiritual and political roles, Zanabazar was a prodigious sculptor, painter, architect, poet, costume designer, scholar and linguist, credited with launching Mongolia’s seventeenth century cultural renaissance. He is best known for his intricate and elegant Buddhist sculptures created in the Nepali-derived style, two of the most famous being the White Tara and Varajradhara, sculpted in the 1680s.

Zanabazar used his artistic output to promote Buddhism among all levels of Khalkha society and unify Khalkha Mongol tribes during a time of social and political turmoil.

To make it easier to translate sacred Tibetan texts into Mongolian, he created an entirely new script, called Soyombo, and although it is barely used today, one of its letters, the Soyombo, became a national symbol of Mongolia.

He even (long after his death) had a dinosaur named after him.

Geser

Geser, fearless lord of the legendary kingdom of Ling, is the hero of one of the greatest and most widespread Mongolian epics. In most of the various tales, he has a miraculous birth, a despised and neglected childhood, and then becomes ruler and wins his (first) wife ‘Brug-mo through a series of marvelous feats.

In the Buryat versions of his epic, the infant Geser defeats giant rats, human-sized mosquitoes and steel ravens before he grows up to kill a series of monsters and demons that have grown out of the various body-parts of the dismembered Atai Ulan, khan of the malicious gods of the East.

Instead of dying a normal death, Geser departs into a hidden realm from which he may return at some time in the future to save his people from their enemies.

Sorghaghtani Beki

Sorghaghtani Beki, Kublai Khan’s mother, was one of the most competent and powerful leaders in the Mongol Empire, and is thought to have been one of the most influential women in the history of the world.

Though she never ruled over the Empire in its entirety, she was granted enduring leadership over a sizable portion of it after her husband’s death and became empress of the pax mongolica.

She repeatedly rejected marriage proposals from Ögedei Khan, saying that her sons needed her attention; each of her sons learnt a different language, corresponding to a different region, and all of them grew up to be leaders in their own right.

She was a Christian, but she gave charity to both Christians and Muslims; she was tolerant of religious diversity, and her sons carried on this trait.

Khutulun, the Wrestler

The great great granddaughter of Genghis Khan, princess Khutulun is remembered for martial prowess that was striking even in a martial society. In battle she fought beside her father, Lord of the Odegai, her deft equestrian skill making her a deadly combatant. Marco Polo met her and wrote that she would “make a dash at the host of the enemy, and seize some man thereout, as deftly as a hawk pounces on a bird, and carry him to her father, and this she did one man a time.”

But it was in the wrestling ring that she won eternal fame.

Blessed (or cursed) with fourteen brothers, Khutlun emerged as a precocious wrestler in her youth. As she came of age as a noblewoman, she demanded her suitors prove themselves to her by wrestling her. As her fame grew, she attracted many suitors who presented herds of horses, either as dowries should they best her, or forfeit should they lose.

No prince was able to throw Khutlun, and she amassed a sizeable herd of horses. Ultimately, she chose her own spouse, a noble warrior from her father’s horde. She thus retired on her own terms, undefeated, immortalized in scores of oral legends, novelizations, and even an unfinished Puccini opera.

Jianggar

Jianggar is the hero of one of the great Mongolian epic sagas.

It is said that his father established a Utopia known as Baomuba, a place where there was no orphan, no widow or widower, where people never went hungry, and where they were never older than eighteen years of age. When the crown of Baomuba passed to the third generation, the queen gave birth to a baby who was ensconced in a red ball. It was the boy Jianggar, who was so strong and powerful that as soon as he came into the world, he was able to speak and to kick a big hole in the old goat skin mattress he was lying on.

His father was so pleased with the birth of his son that he began neglecting attention towards the defense of his kingdom. Manggusi, a monster, invaded the kingdom and Jianggar’s parents were killed when he was two years old, leaving him an orphan.

To avenge his parents’ murder, Jianggar began to go out to battle at the age of three. When he was seven years old, he had established his fame and had become the King Khan of Baomuba. Despite being defeated several times in war, Manggusi did not relent in his invasions of Baomuba. Leading 35 generals and 6,012 warriors, Jianggar defeated Manggusi and kept Baomuba free from invaders’ occupation.

THE MONSTERS

What would a mythology be without its monsters? What would a game be without combat? Here is the Most Wanted list of monsters and demons we have found in Mongolian epics.

Mongolian Death Worm

A vast, poisonous worm of the Gobi desert, called olgoi-khorkhoi. Like the sandworms in Dune and Tremors, it travels underground and can kill at a distance, either by spraying poison or by electrical discharge. Most active in summer, and when the ground is wet. Preys on camels and lays its eggs in their intestines. Corrodes metal, and is attracted by the color yellow.

Manggus

The great many-headed monster-demon of Mongolian mythology that killed Jianggar’s parents and invaded his kingdom, forcing him to go to war at the age of three.

Atai Ulan

King of the malicious gods of the East, defeated and dismembered by Tengri so he could not reincarnate. But each of the severed parts of his body became different demons and monsters, and Geser had to fight them all one by one.

Gal Dulme

A human volcano, born from Atai Ulan’s corpse.

Abarga Sasen

A 15-headed demon born from Atai Ulan’s right leg.

Shiram Minata

A demon from the country between Life and Death, born from Atai Ulan’s left leg.

Arkhan the Sun-Eater

A great beast born from Atai Ulan’s severed head.

Orgoli

The giant Tiger-Lord of the Taiga, born from Atai Ulan’s right hand.

Steel Raven

Attacked the epic hero Geser in his infancy. Did not fare well. Notice the parallel with Hercules strangling snakes in his crib.

Giant Rats

Who also attacked Geser in his infancy. The rats fared no better than the Steel Raven.

Human-Sized Mosquitoes

The third of the creatures that attacked Geser in his infancy. Went the way of the Steel Raven and the Giants Rats.

THE SACRED/MYSTICAL SITES

The game takes place within the approximate borders of the Mongol lands. This territory is neither the full extent of the Mongol Empire at its largest, nor is it limited to the present-day country of Mongolia. It corresponds to a time and a place—part historical, part contemporary, part fact, part fiction–where the Mongol people and their traditions are most vividly alive.

Each of these locations—closely based on fact or mythology—acts in the game as a sacred site for two of the gods. Like their nomadic counterparts, the champions move from location to location with the seasons. Their final destination is the summer festival of Naadam.

The importance of the sites within the game is explained in the rules, still to come. The sites will be mapped onto the game mat, which is also the bag that holds the game–a suitable container and method of transport for a nomadic culture.

Uureg Lake

Uureg Lake is a taboo place, best thought of little and visited less.

It is a source of freshwater in land where water is precious, but the people of the Uvs Nuur Basin rarely drink from it, and never bathe in it. It holds a bounty of edible fish in its depths, but the nomadic Tuvan People rarely fish from it, and never from a boat.

Large shadows move swiftly below its surface, suggesting the presence of something much larger than expected species. Modern geologists and hydrologists have suggested that certain of the currents in Uureg are the result of underground channels that connect the lake to other, larger, deeper, bodies of water in the Basin. Blurred photographs purport to show what the Tuvans have long known–that a plesiosaur-like creature has somehow defied time in this remote environment. Believers argue that the possibility of an interconnected warren of aquatic caves make the basin uniquely suited for hiding and protecting a population of lake monsters; nearby lakes provide depth enough to stay hidden, and a hypothetical cave system provides access to the rich, unfished food source of the Uureg.

Burkhun Khaldun

The Tuul River Basin waters an area of tens of thousands of square miles, and has also nurtured centuries of the region’s musical poetry tradition. The Tula changed little over the centuries but depending on the author’s subject it could assume many guises. In The Secret History of the Mongols, for example, it is peaceful, but also dark and deep as the impenetrable forests that hid the imposing fortress of Torghul, the brooding ally of Genghis Khan.

Rising above it stands the sacred mountain Burkhun Khaldun. Aside from hosting a rich array of flora and fauna, and purportedly hiding both Genghis Khan’s birthplace and tomb, Burkhun Khaldun is the ancient and inviolate link between Mongolia and Heaven. Prehistoric chants, classical literature, and modern orchestral hymns all praise the majesty of the holy peak.

The Sacred Eight White Yurts of the Darkhads

For centuries, speculation and excavation have centered on discovering the tomb of Chinggis Khan. His final resting place remains unknown, but for the Darkhads of northern Mongolia, the quest to find Genghis Khan’s physical remains is an insignificant and unimportant task compared to the sacred trust of their people: the eternal safeguarding of his spirit.

When Chinggis Khan was prostrate on his deathbed, a shaman came unto him and performed the cindariin hurrcag rite. He guaranteed that the essence of the dying lord would live forever with his people by capturing a fragment of the departing soul in a camel’s hair. After death and burial, Genghis Khan’s spirit relic, and other holy artifacts associated with his life and deeds, were entrusted to the shaman’s people for permanent conservation.

For nine hundred years, the Darkhads kept their sacred oath.

Historically the Darkhads were nomadic dwellers of the Steppe. They followed grazing sheep herds and game animals across the broad northern plateau; moving quickly, often, and far, was the Darkhad way. Yet wherever they went, the first and central fixtures of the camp were the Eight White Yurts. In these tents the Darkhads kept permanent watch over the spirit and regalia of the great Khan, guarding watchfully, offering regular sacrifices.

For nine centuries, though the position of the yurts shifted with the seasons, they were the numinous locus of northern Mongolia.

Caves of the Thousand Buddhas

Dunhuang, a small city known for its well-preserved archaeological sites, was a stop on the ancient Silk Road, and boasts structures and artifacts that date to as early as 2,000 BCE: Buddhist, Christian, Manichaean, and Jewish texts and artifacts can be found comingled in hidden alcoves of crumbling ruins.

The epitome of this mixed ancient repository is the Mogao Caves. Known locally as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, this sprawling grotto complex holds hundreds of temples, a recently rediscovered eleventh century library, ornate murals and monolithic stone Buddhas.

Hidden in an antechamber adorned with abstract designs seen nowhere else in the cave system, researchers discovered a cache of documents belonging to a high-ranking monk of the Mogao that reveal a grim business—that of individuals selling themselves into slavery.

Though the practice was ostensibly forbidden at the time, those with means regularly purchased the lives of commoners in desperate situations. In one record, both the buyer, one Chidar, and the signatory witness, one Darughachi Ked, were Mongolian. Chidar remains faceless, but investigations have indicated that Darughachi Ked was one of ninety-five vassals listed in Secret History of the Mongols as being appointed by Chinggis Khan to rule over his territorial holdings.

The Burial Mounds of Noin-Ula

Following the course of the Selenga River in northern Mongolia, a swath of land is characterized by tall mounds–the preserved mausolea of the ancient Xiongnu aristocracy.

The Xiongnu of the eastern Steppe was an alliance of nomads that through pluck and diplomacy was able to remain independent from the khanates and empires surrounding them. This proud confederation produced lineages of statesmen and noble knights whom they honored by interring them in the hills near the life-giving Selenga.

The climate of the region is such that extreme temperatures below zero often follow floods. This combination results in a process whereby the corpses within the tombs were effectively flash-frozen annually, slowing the process of deterioration. Modern excavations have uncovered human remains with skin still intact after two thousand years, lacquerware with decoration still legible, and even textiles.

On these textiles can be found the epic cycles of Xiongnu. Detailed tapestries depict the deeds of cavalrymen, priests performing religious rites, and the life stories of the dead in their burial mounds.

Ulaan Tsugalan

In the geographic center of the Mongolian Plateau, a wide valley recapitulates the four distinct elements of the Mongolian landscape: arid desert, evergreen forests, sacred peaks, and wide rivers. From a single viewpoint an observer can see the distant rise of Mount Otuken where ancestral spirits dwell, a band of emerald copses at the mountain’s base, an expanse of tawny dunes, and the deep sapphire of the winding Orkhon River connecting them all. Since at least the eighth century this has been a site of inspired verse. Artisans of the Bilga Khaganate, which once ruled this land, chiseled tales of the Orkhon onto monolithic stele that are still standing in the valley. However, centuries later, the Qitan nomads claimed the valley, and re-inscribed the ancient stele with their own stories.

The true nature of the Orkhon is embodied in the Ulaan Tsugalan waterfall that roars in the valley’s heart. During dry seasons, the cataract is waterless, silent, and empty; it could be mistaken for a dramatic cliff. When the rains come, the Orkhon River swells, and Ulaan Tsugalan (“The Red Falls”) turns into a furious ensemble of thunder and mist. According to the verses of the standing stones, the falls are a metaphor for the Orkhon’s human history, centuries of peaceful life punctuated regularly by violent competition and cultural displacement.

The Whistling Dunes of Dalad Banner

Backed by the Kubuqi Desert, Xiangshawan (“Whistling Dunes Bay”) consists of crescent-shaped sand dunes that rise to a height of 90 meters at a gradient of 45 degrees.

During dry weather, the sand inexplicably vibrates when disturbed. Sliding down from the slopes of the dunes, one can hear not only whistling but the cry of a bugle, the beat of a drum, even the noises of automobile and aircraft engines.

If several people are surfing together, the sound will be as loud as a large bell, and it feels as though the whole dune is trembling.

Naadam

Naadam is one of the oldest festivals in the world, a combination of holiday, military parade, feast period, and athletic competition that predates the Olympics by some 700 years.

Its origins lie in the celebrations, including athletic contests, that followed weddings or spiritual gatherings. Mongols practice their unwritten holiday rules that include a long song to start the holiday, then a Biyelgee dance. Traditional cuisine, or Khuushuur, is served along with airag, a drink made of fermented mares’ milk.

The main contests feature the three traditional Mongol sports: wrestling, horse riding, and archery.

The largest Naadam festival is held in the capital, Ulaanbaatar, where Chinggis Khan‘s nine horse tails, representing the nine tribes of the Mongols, are still ceremonially transported from Sukhbaatar Square to the Stadium to open the festivities. At the opening and closing ceremonies, there are impressive parades of mounted cavalry, athletes and monks.

Naadam is a time of trading and bartering, when deals are struck and alliances formed. Other popular Naadam activities are the reciting of epic ballads and tales, and the playing of games using shagai, sheep’s anklebones that serve as game pieces and tokens of both divination and friendship.

THE SHAGAI

Each shagai has four faces; each face has a traditional name. Here is a short video showing them. In the game Ulus, they are more than dice–they are the player’s access to good fortune, even their means of communicating with their god. More information on the use of the shagai will be included in the rules.

THE RULES

Overview

The Mongolian word “Ulus” means empire, nation, or home.

Ulus: Legends of the Nomads begins with the Mongolian gods. In our fictional version, the gods all have their own notions of Ulus—that is, their vision for the future of the Mongol lands and the Mongol soul–and, like the Greek gods, they play out their arguments on the human chessboard, and can be remarkably petty and even cruel in playing with their human pawns. Each god (working through the player) chooses a champion who will fight for that god’s Ulus.

Players

2-6 Players, ages 10-adult.

Duration

45-75 minutes.

Goals

Each god (working through the player) chooses a champion who will compete to acquire the assets their god needs in order to establish their own Ulus. The goal is to acquire 20 points in assets by the end of the game, while fighting off attacks by monsters and by the other players.

The exception is the trickster god Lobsogoi, who has no aim but to mess with the other gods and defeat their ambitions.

Game equipment

8 God cards

8 Champion cards

24 Monster cards

24 Asset cards

3 Eternal Blue Sky cards

Game mat/map of 8 sacred locations within the Mongol lands.

10 Shagai

Each god card identifies the god’s strengths, their particular sacred sites on the game map, the assets that god needs in order to establish their own Ulus, and their particular form of divine intervention in the game—an apocalyptic act that can be used only once. The exception again is Lobsogoi: a shape-shifter, he can mimic other gods’ strengths and their acts of divine intervention.

Champion cards identify the character from Mongol history or mythology who will try to carry out their god’s bidding during the game. Champion cards are player strengths, weaknesses, and advantages. Champion Strength and Spirit values are balanced so that none is inherently better than another, but each champion is uniquely suited to a different Naadam game. Each champion is also associated with their own totem animal—that is, their own particular face on the shagai.

Monster cards identify figures from Mongol mythology who threaten the champions but can also be defeated, tamed, and used against other champions.

Asset cards identify features of traditional Mongol culture that may be essential to establish each god’s vision of Ulus. Each asset card has a value that varies depending on the player’s goals—some assets are more valuable than others in pursuit of a particular Ulus.

Eternal Blue Sky cards are wild cards that, once acquired, cannot be traded or stolen.

Each shagai has four faces, traditionally identified as Sheep, Goat, Horse, and Camel. Each champion has one of these four animal-faces as their own totemic animal, and there is special spiritual value in a roll that lands with that face upwards.

The game mat is a semi-factual map of the Mongol lands, featuring eight sacred sites the champions will visit, seven of them during the first, or Nomadic phase of the game, and the last for the second, Naadam phase. Each location is connected to a particular god or gods, and thus has its own power that may work for or against each champion. It also has a “normal” function when a player lands on it, and a “sacred” function if a player lands on it by rolling their champion’s totemic animal.

Examples: Sacred Yurts of the Darkhads

Theme: people, protectors

Normal: Take 2 random cards from another player and exchange them with 2 of your own

Sacred: Trade hands with one other player

Burkhan Khaldun

Theme: life, holiness

Normal: If attacked this turn, survive death and lose no assets

Sacred: Redirect any attacking threat this turn toward any other champion, regardless of the initial target

To start the game

The game mat is laid out—either on a table, or players can go full nomad, place the mat on the ground, and sit or squat on the floor around it.

The God cards are shuffled and randomly distributed. A player’s god is kept hidden or face down. Players then choose a Champion card. If two or more players want the same Champion, they compete for that Champion’s favor by rolling a shagai at the same time. The first player to roll that Champion’s totem (the animal printed on the Champion’s card) wins.

Unused Champion and God cards are placed face down in a separate pile. Eternal Blue Sky cards are placed to the side.

Asset and Monster cards are shuffled together and each player is dealt a hand of 9 cards. The remaining cards are placed facedown as a deck next to the mat.

Each player will want to build a hand that consists of Asset cards and Monster cards that are of particular value to their own quest. The Monster cards in one’s hand are in a sense tamed, and have become weapons that in due course can be used in Combat against other players, or in defense, or may be discarded. The Asset cards may be of value to the champion, or not. In due course they may be discarded or traded with other players for other Asset cards.

The game is now ready to begin.

Game Phase One: the nomadic phase

The Mongols are traditionally nomadic people, so the first phase involves seasonal travel. The aim of this phase is to travel around the Mongol lands, visiting sacred sites that will help each player to build up as strong a hand as possible before arriving at Naadam, the great summer festival of the Mongols. A strong hand will consist of a blend of valuable Asset cards and Threat cards. Each player will also want to arrive at Nadam in as strong and healthy a state as possible, so part of the aim in the nomadic phase is to repel any threats and to heal from any conflicts.

The round

Each player in turn rolls a shagai on the game mat, aiming for a particular location that will be valuable for their quest. They follow the instructions associated with that location.

Next each draws a card from the Asset/Monster deck without showing it to the other players, and discards one of the cards from their hand.

Once every player has picked up and discarded, the player to the left of the dealer may choose one of three courses of action: check, trade or attack.

The check involves simply tapping their hand on the table and passing the choice on to the next player.

If a player decides to trade, they call on a specific opponent and ask for a specific Asset card, in the manner of the game Go Fish, for example: “Do you have the Eagle?” “Do you have the Horse?” If the opponent has that card they must turn it over and receive an Asset card in return. If they do not have that card, no trade takes place.

The attack involves pitting one’s own monsters again another player’s. Each Champion has Strength and Spirit, equaling 10 for each character. Strength is the ability to attack characters, Spirit is the capacity to take hits. You can attack another player by playing a monster, which will add to your Champion’s Strength stat. The defending player can play a monster of their own, which will add to their Champion’s Spirit stat. The attacking player can then decide to boost their Strength further by adding in another attacking monster, and the defending player can do the same by adding another monster to their Spirit, until either player runs out of monster cards or one chooses to accept defeat.

If the attacking Champion’s strength is higher than the defending Champion’s spirit by the end of the battle, the attacking player wins. Otherwise, the attacking player loses.

The Champion who loses the battle must discard an asset card (if they have one) and both Champions must discard any monster cards used.

If there is a draw (even strength vs spirit), both players must still discard any monster cards used but do not need to discard an asset.

Battles can’t commence unless using a monster.

After seven rounds, corresponding to seven consecutive seasons of travel around the Mongol lands, the players arrive at Ulaanbaatar for the summer festival of Naadam, and the second phase of the game begins.

Game Phase Two: Naadam

Naadam itself is described above. In our fictional version, Naadam is the time and place of the showdown.

The traditional Mongol sports

These minigames each represent real Mongolian shagai games (with archery being the most modified).

Naadam games go in the order of Archery, Horse Racing, then Wrestling. The winner of each game earns an Eternal Blue Sky card, which is an unlosable special asset worth 5 points.

Archery

Based on accuracy-focused shagai flicking games.

The archery game is 5 rounds. Goal is to win the most rounds. Player with the most cards starts.

Each player takes a shagai and, starting from the edge of the mat, takes turns flicking their shagai toward the center circle at Ulaanbaatar.

Like curling, the player closest to the center of the mat wins the round.

During the next round, the player who won the previous round goes first and play continues clockwise.

Knocking away opposing shagai is allowed

Whoever wins the most rounds wins the match and earns an Eternal Blue Sky card.

In the result of a tie, the tied archers have a tiebreaker round.

Three of champions are able to redo their shot once per round: Zanabazar, Beki, Tuul’ch.

Horse Racing

Based on the “Horse Race” shagai game.

The horse race game is 1 round. Goal is to reach Ulaanbaatar first. Player with the fewest cards starts.

All players take a shagai, turn it to their Champion’s totem, and place it at the starting point, Uureg Lake.

Locations on the mat are in a nautilus pattern and follow the order: Uureg Lake > Sacred Yurts > Burkan Khaldun > Burial Tombs > Whistling Dunes > Mogao Caves > Red Waterfall > Ulaanbaatar.

Players take turns rolling 4 shagai — the number of Horses rolled equal the number of locations/spaces they move their shagai forward.

The winner is whoever reaches Ulaanbaatar first.

In the result of a tie, the two fastest horses have a tiebreaker round.

2 champions start with a 1 space head start | Chinggis, Jianggar.

Wrestling

Based on matching-focused shagai flicking games.

The wrestling game is 1 round. Goal is to capture the most shagai. Player with the fewest cards starts.

Shake all shagai and drop them onto the center of the mat.

Flick any shagai into matching shagai to capture the one you hit.

If there are no matching shagai, re-roll all remaining shagai until a match is present.

If there are only two shagai left, you can hit the opposing shagai regardless of if it matches.

The game ends when there is only one shagai left. The player who captures the most shagai wins.

In the result of a tie, the two highest scoring wrestlers have a tiebreaker round.

2 champions start with a 1-shagai lead | Geser, Khutulun

Optional fouls (based on the rules of traditional shagai matching games). Doing any of the following ends your turn and cancels any capture:

Pushing shagai (you can only quickly flick them)

Hitting non-matching shagai

Hitting walls or falling off the mat

Using a hand to capture a shagai that is different from the one you used to flick (they must be the same hand)

Endgame

At the end of the Naadam games, players tally the points on their asset cards, including any sacred asset multipliers and Eternal Blue Sky cards. The player with the most points, provided they reached at least 20 points, wins. However, if no player reaches at least 20 points, Lobsogoi wins — even if he was not in play.