Kadazandusun, or Pimato: the case for a new Malaysian script

A surprising (to me) number of people still wonder why someone would go to all the trouble of inventing a new script for their language when, as they see it, the world seems to have enough perfectly good ones going around. Let’s hear the answer, or some of the answers, from the source. A guest column by Ander Volintine.

A neography is a term used to refer to invented writing systems. The label might sound redundant as all writing is invented. However, neographies are specifically writing systems that are designed usually by not more than two people. The most widely-used neography today is Hangeul for writing Korean, having been invented by King Sejong, and proclaimed in 1443. Another notable example is the Cherokee syllabary, invented by Sequoyah circa 1810.

One doesn’t have to be literate to invent writing. Sequoyah was only literate in his own Cherokee syllabary, having been inspired by the ‘talking leaves’ white men used which sparked his interest. Another example of a neography created by someone illiterate was the script created by Tenevil, a Chukchi farmer and reindeer herder. These cases call to question as to how many times did pockets of people around the world independently invent writing, only to eventually forget it?

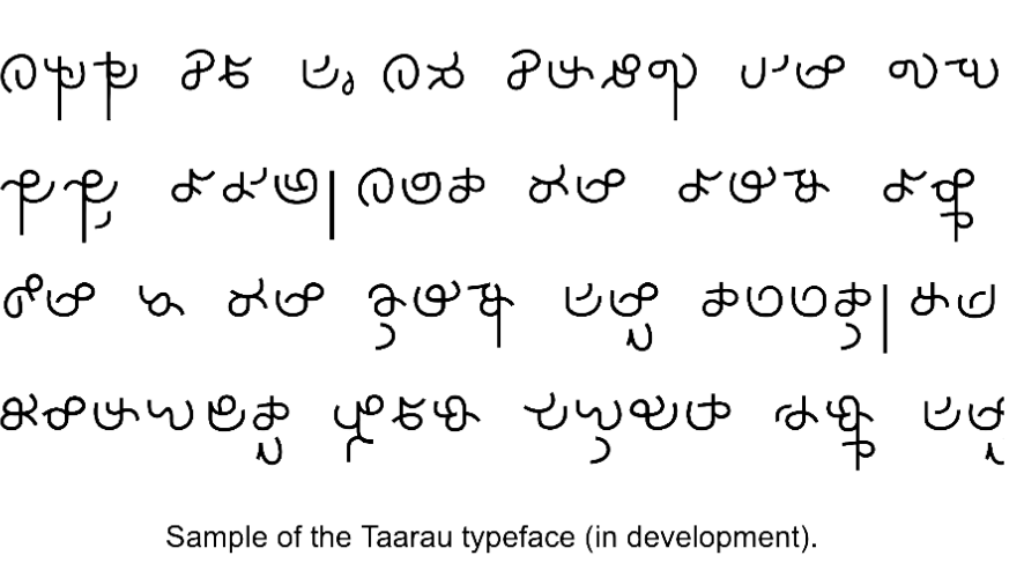

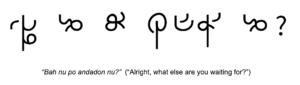

Seven years ago, at the age of 13, I took it upon myself to invent a writing system for my native language, Kadazandusun. As I would eventually come to realize, the story of an odd member of a minority group inventing a writing system is actually not uncommon. I would not be the first person to invent a neography for Kadazandusun, nor (I think) would I be the last, but my script is the first to have been born in the age of artificial intelligence, in a world more connected than ever. I could not settle on a name for this script, and eventually resorted to simply calling it Pimato which generically means “letters” or “characters.”

Before going further, I would like to introduce my people and myself.

My people call themselves the Kadazandusun, among other names (the older generations are actually still arguing about what to call ourselves). According to the Malaysian Department of Statistics we number just a little bit above 700,000 people, making up about 2.1% of the Malaysian population. We are a loose confederation of tribes that share a dialect continuum and more or less the same culture, stories, and history. We make up the largest indigenous group in Sabah (formerly North Borneo), an autonomous region within the Federation of Malaysia. Though in search of hopes and dreams, we form small diasporas within and outside of the federation, mostly in Malaya (Peninsular Malaysia), and Australia.

My name is Ander and at the time of writing I’m in my second year of undergrad, studying electrical engineering at Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP). I cannot understate how lucky I was to have been awarded a scholarship by the state petroleum company to further my studies. As a native, there were other avenues via affirmative action programs, but nonetheless being able to study at UTP instead has changed my life in ways I never could have thought. Going back to the topic, from the moment I learned the Latin alphabet, I’ve always been curious about the concept of writing.

I remember this particular pre-kindergarten memory that must have been back when I was 5-6, when I was staring out of the car window looking at signage passing by. Of prominence were letters that I could read, but interspersed with squiggles that I later found out to be Chinese. It was incredibly interesting to me back then (and still now) that people had more than one way to write. As I grew up, sometimes the first introduction I had to an other people was via how they wrote. Dense, blocky characters are Chinese. Blocky, sharp characters are Korean. Squiggly noodles are Arabic. Writing isn’t just a practical way to convey speech into the visual modality. It was quite literally a manifestation of the culture and identity of a people.

It doesn’t feel fair that only few peoples can afford the luxury of having their own script. The Latin script isn’t ours, it was never ours and didn’t feel like it can ever become of us. There is nothing that can stop the Kadazandusun from having a script, proudly of their own. Being familiar with the language’s phonotactics, I settled on a hybrid abugida-syllabary, where each open syllable is a ligature, enabling effortless writing. Like Hangeul, final consonants are written at the bottom of an open syllable glyph. The letter shapes were chosen so that they may all have a vertical stem like Mongolian (except Pimato would mostly be written horizontally, but vertical writing is possible).

The design requirement of having a common vertical stem present in all letters is inspired by tendril motifs extremely common in Kadazandusun traditional art. From sininggazanak statues, to beadworks, textiles, brassworks, and carvings on musical instruments, most patterns seem to diverge from a central stem. In a poetic way, the story of each consonant is told by a common origin, the stem, out of which numerous sounds, and finally a language, is formed. Fittingly, this interpretation matches up with the tale of Nunuk Ragang, detailing the origin of our different tribes and their migration out of the Nunuk Ragang settlement.

Having one’s own script does more than just typographical differentiation. When a language has its own script, the script gives access to another dimension of expression where speakers of the language are empowered to tell their perspective, their history, and their culture through the written word. Loaning another script impedes access to this dimension. There is also the irony of linguistic diversity being represented in writing in a way against graphemic diversity. Most of the world’s threatened and endangered languages are written in the same, conspicuous script, more often than not only adopted due to colonialism, convenience, or both. A language equipped with its own script is more powerful than it sounds. When written, the same effect generated by its sound is reproduced by its look.

Having one’s own script does more than just typographical differentiation. When a language has its own script, the script gives access to another dimension of expression where speakers of the language are empowered to tell their perspective, their history, and their culture through the written word. Loaning another script impedes access to this dimension. There is also the irony of linguistic diversity being represented in writing in a way against graphemic diversity. Most of the world’s threatened and endangered languages are written in the same, conspicuous script, more often than not only adopted due to colonialism, convenience, or both. A language equipped with its own script is more powerful than it sounds. When written, the same effect generated by its sound is reproduced by its look.

As of now few people know the existence of Pimato, and only its creator knows how to read and write in it. But it is too early for Pimato to gain users, since I’m still developing the first typeface for it. As of right now I’m concentrating on preparing the digital infrastructure of the script. I’d spare the technical details, but preparing a script for the digital space is incredibly tough especially without the script being encoded in Unicode (yet). My plan is to eventually promote the script on social media and create a digital presence for it. The script would be featured in Instagram posts, karaoke sing-along videos, blog posts, documents, infographics, and more.

I’m confident that the younger generation, especially Gen Z would have a renewed interest in their mother tongue. Intergenerational transmission of Kadazandusun is threatened due to competing languages such as Malay, English, and even Mandarin (Chinese-medium schools in Sabah are actually majority non-Chinese). What I’ve noticed growing up is that Japanese and Korean cultural exports include Kana and Hangeul, which seem to be primary motivators for the younger generation to study Japanese or Korean. I’m hoping that Pimato would have the same effect to excite and motivate young Kadazandusuns to learn their ancestral tongue, lest it be gone forever.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.