Missing in Action?

As I’m sure you can imagine, I spend much of my time (and my amazing volunteers spend much of their time) looking for scripts that have little or no Internet footprint, that may or may not still exist, that may be symptoms of marginalized or even oppressed cultures, forced to live out on the fringes, their identity and autonomy being eroded with each passing day.

So I’m particularly interested in a script referred to as Rma, Rme or Qiang, created about 10 years ago for a community—a divided community, perhaps even two communities—on what used to be the borders of China and Tibet, in Ngawa Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture.

After two years of hunting, I’ve found only two pieces of evidence.

The first, remarkably, may be the script’s creation story. It’s a Duke University master’s thesis, “The Creation of the Qiang Ethnicity, its Relation to the Rme People and the Preservation of Rme Language” (undated, but probably 2014), written by a young man who seems to have two versions of his name, presumably a Tibetan and a Chinese version, as he is identified as Maotao (Tsering) Wen (Bun).

He grew up, he writes, understanding that he was a member of an official ethnic minority called “Qiang.” Over the past three years, though, he came to understand that the Qiang ethnicity, as constructed and promoted by the government, is in essence artificial, consisting not only of the Rme-speaking people who were the core of the minority designated as Qiang, but also many Han Chinese reclassified as Qiang since the 1980s—perhaps part of the Chinese government’s ongoing efforts to sculpt and mold the country’s ethnic minorities into acceptable sub-groups that don’t threaten the uniformity of the country as a whole.

“The newly constructed Qiang ‘exhibition’ culture, invented in part for tourism, threatens to displace the culture of this core group of Rme-speaking people.”

One major part of this act of social and cultural engineering was the creation, in the 1980s, of a Qiang script, based on the Qugu variety of a Northern Qiang dialect, using the Latin alphabet. (The Chinese have created a number of scripts for minority languages, showing a curious penchant for extensions of the Latin alphabet.)

“In general,” he writes, “promotion of this system was not very successful.” The letters did not jive well with the complex sound system in Rme language, and were themselves difficult to learn “since most of Rme speakers are illiterate peasants.”

In addition, the Latin-based system had the effect of alienating “a very important group of Rme language speakers, the Tibetan Rme in Heishui County. As a result, the target people for this script shrank over 50%.”

His solution: to create a new script for the Qiang that celebrates both their Rme/Rma heritage and their Tibetan roots.

“Since language is a key basis for any Rme-speaking identity, language preservation offers one of the few ways to resist this process.

“[I]n order to preserve and record Rme language in Heishui, creating a writing system is necessary and urgent. It will not only provide a new writing system for Rme (under the name of Rme and not Qiang) but it will have a positive impact in preserving diversity within the Tibetan culture. Another important potential benefit is that it could be used as an educational tool in elementary schools to address the language barriers that young Rme students have.”

His sensible but radical step was to base the new script on the Tibetan orthography, adding nine additional letters to the traditional Tibetan alphabet.

“[A]s a historically Tibetan Buddhist influenced area, Tibetan letters have been used in this area for hundreds of years. Rme people in Heishui County share cultural and ethnic identities with other Tibetan ethic groups on the Tibetan Plateau. In additional to this, the Tibetan alphabet has already been successfully been developed for different platforms including smart phones. This would be an advantage in the future script promotion. Therefore, I have been working to develop a script based on the Tibetan letters/script.”

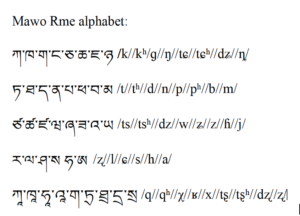

The core of the resulting script looks like this:

All of which is fine in theory, but what happened next? Was his invention used? Was it taught? Was it even allowed?

The only other cluster of evidence is a YouTube channel consisting of five well-produced videos (two of which are different versions of the same item) uploaded between 2016 and 2022 by one Jiuqiao Wei, introducing the script he calls Rma:

A 2016 video about Rma Chongcao Diggers, with text in Chinese and Rma

A video introducing and promoting the Rma script, uploaded in 2017 and reuploaded in 2022

Alphabet of Rma/Qiang script, 2020

The story of Rapunzel in the Qiang language using the Rma script, 2020

After that, output or upload seems to have ceased. Is the script referred to in the videos the same as the one in the thesis, or are they two different alphabets? They certainly don’t look exactly the same, but the chances that we’re looking for two missing Rma scripts….

Tim

Breaking news: we are in fact looking at two different scripts, and I’ll be bringing you a lot more information about the second script soon. But there’s still a mystery–namely, what happened to the first script? I’ll be bringing you more about that, too, though the situation is far from resolved…..

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.

July 11, 2023 @ 11:07 am

I just discovered the Endangered alphabets project today, and appreciate all the work you guys are doing. You probably have done this already, but why not establish a direct line of correspondence with the two researchers Maotao Wen 文茂韬 and Jiuqiao Wei 魏久乔 so you can get them to provide updates to the atlas when there’s any notable progress? Google searches provide information about ways of contacting them.

July 27, 2023 @ 1:25 pm

I’m glad to say I’m now in email contact!