Alphabets Born of Dreams

It is remarkable how many of the roughly 300 scripts in use around the world have been created in response to dreams—at least 20.

In some instances the dream involved a divine command to create a script for the dreamer’s community; in some cases it included actual shapes to be used as letters; in some cases the dream may have instilled a general sense of purpose or mission; in some cases all of these qualities played a part.

It’s also interesting to see the effect that this dream inspiration had on the dreamer and his (because in every case, it was a man) community. In many cases this revelation or inspiration made the dreamer a man apart, often adding to his charisma and propelling him to a position of spiritual or even military leadership. At the very least, it gave him the conviction to continue his work, which might turn out to be a lifetime of working to teach his letters and try to get his community to adopt them as their script.

The two scripts I have chosen have particular qualities that make them remarkable even in this remarkable tradition. They suggest the extraordinary power of dreams, both for the dreamer and his community.

Vai

The Vai script was created by Mɔmɔlu Duwalu Bukɛlɛ in the 1830s to represent the Vai language, spoken by about 104,000 people in what is now Liberia, and about 15,000 in Sierra Leone. Tradition states that while Bukɛlɛ was working as a messenger on a Portuguese ship, he became curious about the written messages he carried for the crew. How could the recipients understand the captain’s wishes without hearing his spoken words?

When he returned home, he had a dream “…in which a tall, venerable-looking white man, in a long coat, appeared to me saying, ‘I am sent to you by other white men … I bring you a book …’”

In this respect, Vai is also the first of many indigenous African scripts to have been created in response to a dream; and it is fascinating that while the dream figure commanding the dreamer to create a script is usually a deity, Bukɛlɛ’s could either be a white colonial figure or a white colonial god or a combination of the two.

According to Bukɛlɛ, the white man revealed a written script that, on waking, Bukɛlɛ couldn’t remember – hardly surprising, as he had no previous experience with the written word. Given this impetus, though, he called in a number of friends and together they created the symbols that made up the Vai syllabary.

This story about the dream may or may not be true, but it gives a kind of authority to the new script—it makes it a divine expression of an indigenous wish supported by, rather than opposing, the white man’s God and white colonial authority.

Chukwuma Azuonye has written: “Basically psychological is the exciting idea of `a script of our own’ which must be used, even against the odds as an expression of cultural independence. In the 19th century, this kind of cultural nationalist attitude seems to have strongly influenced the great popularity enjoyed by the Vai script among the rural population of the Liberian hinterland. As `a script of our own,’ the Vai script served effectively as a medium of indigenous nationalist reaction against the growing dominance of Americo-Liberian elements in the national life of what was then a new African republic. Everywhere in the countryside, outside Freetown, the true indigenes (tailors, foremen, laborers, housewives, market-women, etc) spurned English and the Roman script and insisted on acquiring literacy in their own script, the Vai script, which they called to use in all transactions of everyday life – fabric measurement, recording lists of workers and their wages, market lists, and for personal correspondence and the keeping of family and private personal records.”

The script remains in use today, particularly among Vai merchants and traders, and in commerce generally. In addition to its presence in commerce, there is a growing body of literature published in Vai: the publication of some small dictionaries, an incubated Wikipedia, a copy of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and translation of historical sources.

During the Ebola crisis, the Vai script was used to promote health and quarantine regulations, both to display warnings and directives on public signage and to distribute messages among Vai communities.

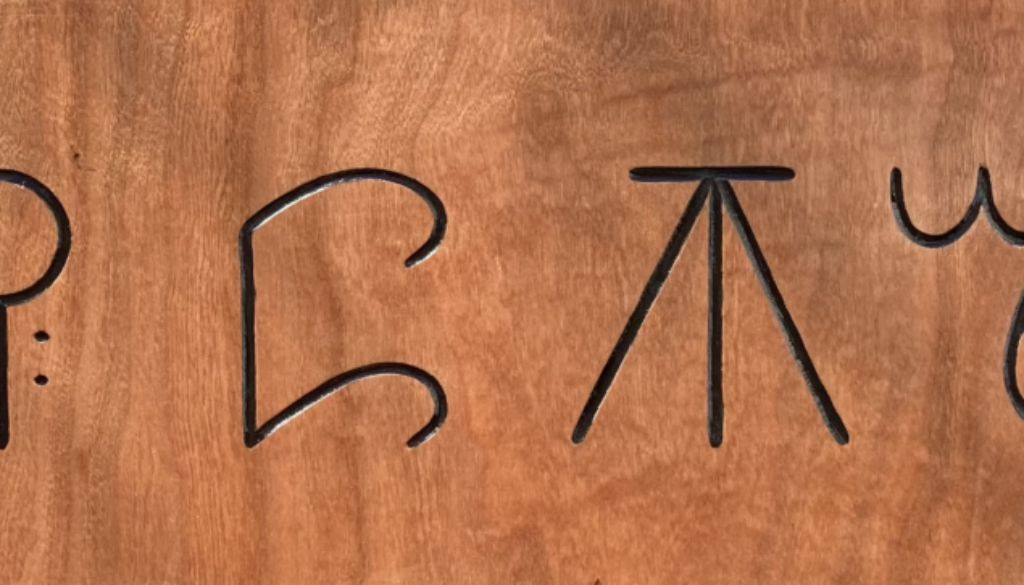

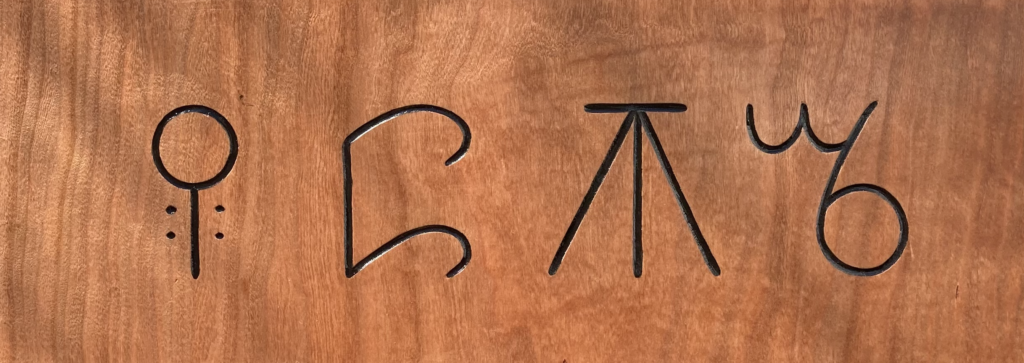

This particular text can be translated as “Long time no see.”

Sora Sompeng

The Sompeng script used by a particular sect of the Sora people of Northeastern India is entirely unique in that it is rarely used for writing and reading—it is used in sacred chanting, and as a feature of household shrines.

As the story goes, on June 18, 1936, a Sora called Mallia “had received a dream showing him where to find a special Sora script magically inscribed on a mountaintop.”

The Sora were an animist people, so their landscape—animals, trees, rocks, rivers—was populated by resident spirits called somums.

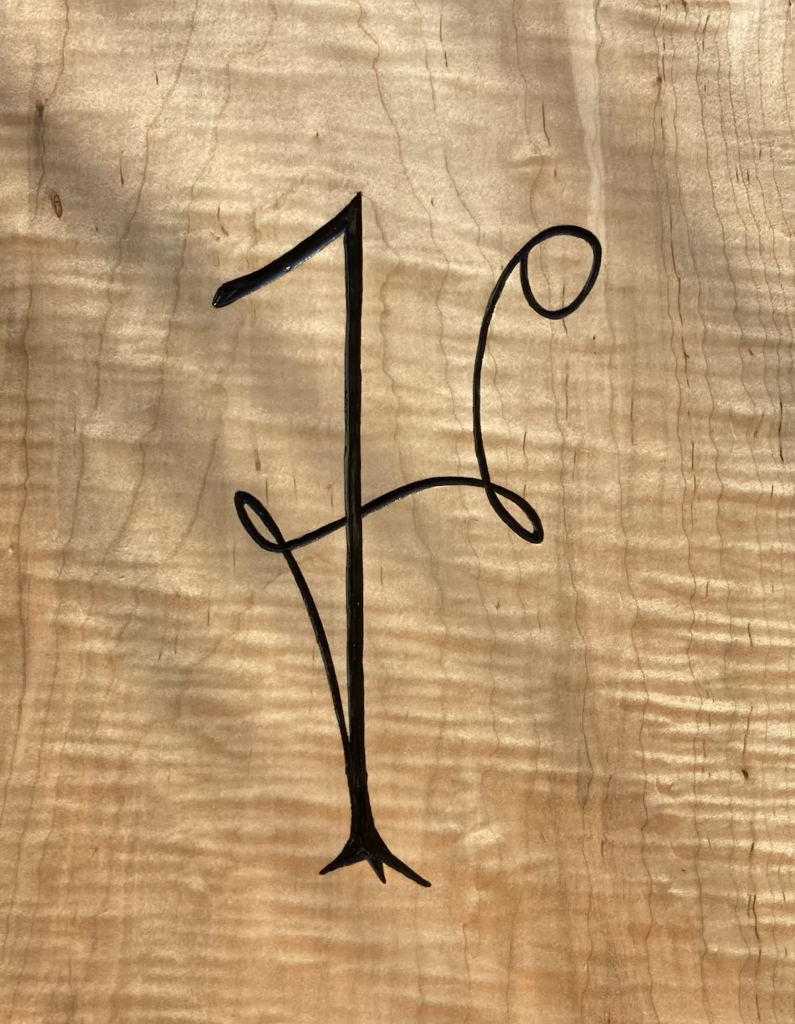

In Mallia’s dream, each of the 24 sonums who populated and made up the Sora spirit world changed into the letter that began the sonum’s name. As such, this collection of letter-symbols came to be known as “script of the spirits” or sonum sompeng, and the individual letters were called nyonan-lipi, which can be translated as “spirit-letters.”

Roughly half of the 24 letters of the script are associated with the initial letter of a particular spirit, so the second letter of the alphabet, /Ta/, corresponds to the spirit of the paths, Tangorsum. The consonant /Ba/ is associated to Babusum, the name given to the tutelary deity of the village.

Other characters do not exactly correspond to sonum/nyonan but to objects or spaces which can be related to them in a ritual context. These elements are not considered as divine agents themselves but represent a contact point between the human world and that of the spirits.

At first Mallia was thought of as crazy, but in time his community accepted him and his thinking, and became known as the “alphabet-worshippers,” or Marirenji, meaning the Pure, Alert, or Clear-Sighted Ones. One of their songs is the equivalent of the alphabet song familiar to children using the Latin alphabet—except that as each of the letters has divine energy, chanting the alphabet has the effect of calling on the spirits of the region.

Individual Sora households have shrines that include the letters of the Sompeng alphabet, not to be read but as ritual objects in themselves.

The letter I have carved is nya, the spirit involved in the ripening of fruit. Given its origins, I have adapted the serif at its foot into the roots of a tree.

Tim Brookes

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque.

April 15, 2025 @ 9:39 am

Very interesting. I have created the Grebo script. Grebo is one of the sixteen tribes in Southeastern Liberia. I don’t have a website yet. There are still challenges.