Women’s Scripts Galore!

At #EndangeredAlphabets I’ve been in the habit of telling anyone who will listen that Nüshu is, or was, the only script to have been invented and used solely by women, but as usual, life is more interesting, and I have been giving out false information. There have in fact been, in one sense or another, at least five women’s scripts.

Wikipedia identifies several of them:

-

- Nüshu, from China.

- Hiragana, from Japan. “When it was first developed, hiragana was not accepted by everyone. The educated or elites preferred to use only the kanji system. Historically, in Japan, the regular script (kaisho) form of the characters was used by men and called otokode, “men’s writing,” while the cursive script (sōsho) form of the kanji was used by women. Hence hiragana first gained popularity among women, who were generally not allowed access to the same levels of education as men, thus hiragana was first widely used among court women in the writing of personal communications and literature. From this comes the alternative name of onnade “women’s writing.” For example, The Tale of Genji and other early novels by female authors used hiragana extensively or exclusively. Even today, hiragana is felt to have a feminine quality.” (If we count sōsho as another women’s script, then, we have 2 (a) and (b) from Japan.)

- Their neighbors, the Koreans, had a similar belief that Chinese characters were superior—superior, in this case, to the hangul script created in the 1440’s. Until well into the 20th century, Korea’s elite preferred to write using Chinese characters, and according to some accounts they referred to the Korean alphabet scornfully as ‘amkeul,’ meaning “women’s script,” though that is of course not to say that only women used hangul.

- The last two of these were, in a sense, not women’s scripts at all, and actually reflect more of a class distinction than a gender distinction. The same cannot be said for the fourth of Wikipedia’s examples–Vaybertaytsh or Mashket, a semi-cursive script/typeface for the Yiddish alphabet. Here the distinction is a complex one of gender, education, language, and religious practice. Hebrew square script was used for classical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, but thanks to gender-based education, women could read only Yiddish—if, indeed, they could read at all. From the 16th until the 19th centuries, then, Vaybertaytsh/Mashket became primary script used in texts for and by Jewish women, ranging from folktales to women’s supplications and prayers, to didactic works. In a sense Vaybertaytsh/Mashket is a women’s typeface rather than a women’s script, but that’s an interesting and unusual distinction in itself.

Wikipedia’s page on women’s scripts stops here, but thanks to the magic of Twitter and the erudition of Thomas Wier, a Caucasologist, (@thomas_wier) we can add a fifth women’s script: Dedabruli.

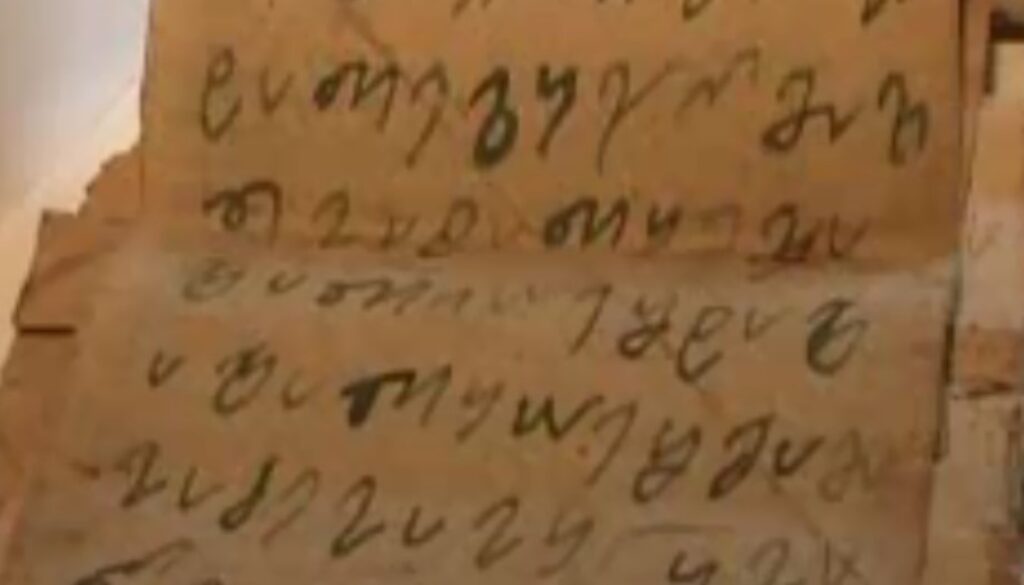

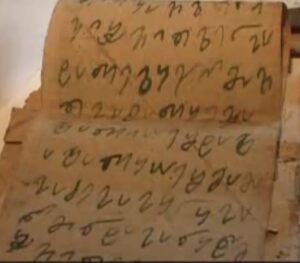

“In Georgia,” he posted, “there used to be a form of script derived from Mkhedruli called დედაბრული ხელი [or] Dedabruli xeli, ‘maternal hand’ used almost exclusively by women from the southwestern Georgian regions of Guria and Ajaria.”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In this case, even though the script was truly a women’s script, the motivation was cultural, religious, and linguistic—another case (see “When Alphabets Are Codes“) of creating a secret script to survive in the face of conquest and suppression.

“During the Ottoman rule,” explains the website of the Khariton Akhvlediani Museum of Ajara, “the population of Adjara was obliged to serve in the Ottoman military service and to wear a compulsory Muslim chador. The chador covered the woman’s face and body. A secret Georgian scrift named `Dedabruli’ was used among old Adjaran women. In this [script], the relatives contacted each other so as not to lose the Georgian language and religion.”

What was this script like? In what way was it encrypted, so to speak? According to the article “The Digital Corpus Of Kobuletian-Adjarian `Dedabruli’ Manuscripts,” it was “a modified form of the Mkhedruli script, with graphical and linguistic characteristics changed for secrecy: angled letters, vowels, not separating words, not using punctuation marks.

That may not sound like the most sophisticated form of concealment, but it suggests two important points: first, that you don’t want a secret script to be too far removed from the written forms that are familiar to the users, or they may find it too difficult to use; and second, that to Ottoman eyes, the Mkhedruli script was already unfamiliar, so it would not have taken much adaptation to make it incomprehensible.

This goes to the heart of the Endangered Alphabets Project in two ways.

First, it shows how deeply connected a culture and its script are that this subterfuge would be seen as so vital: Dedabruli was literally carrying the cultural weight of its users.

Second, the fact that the Ottomans couldn’t read it shows just how hard it is to grapple with unfamiliar glyphs. This is the lesson of my book Endangered Alphabets Sudoku: when faced by a new script, as refugees and new immigrants are every day, the mind tends to go blank.

Dedabruli even turns out to have its own Wikipedia page (in Turkish), which adds a curious additional detail from a 1916 newspaper article: “Georgians who settled in the Old Trabzon village near Athens after the 1877-1878 Ottoman-Russian War were mainly engaged in boating. Women in the village were writing letters in handwriting called Dedabruli heli and delivering them to their relatives in Kobuleti by the hands of these sailor men.”

Not only codes, then, but smuggling?

As for the name of the scrıpt, Dedabruli means “specific to an old woman,” and Heli means “handwriting”—thus Dedabruli heli means “old-woman writing.” Why specifically old, I wonder?

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.