Iban Dunging: Another Writing-Creation, Writing-Loss, Writing-Rediscovery Narrative

Thread 1: My hero, the Australian anthropologist Piers Kelly, has written extensively about cultures, especially in Southeast Asia, that have their own mythic narratives in which they were given writing by a deity, but owing to bad luck, enemy action or their own foolishness, lost it. (There’s a chapter about the topic in my book Writing Beyond Writing.) In many of these stories, they suffered long and grievously for not having their own script, and they long for a hero who will rediscover their writing and give it back to them.

Thread 2: I’ve written about the extraordinary Dayak named Dunging Gunggu, who invented a bewildering number of things including a script for the Iban language in Sarawak. His script is in the process of being digitized, taught, and promoted by Dr. Bromeley Philip.

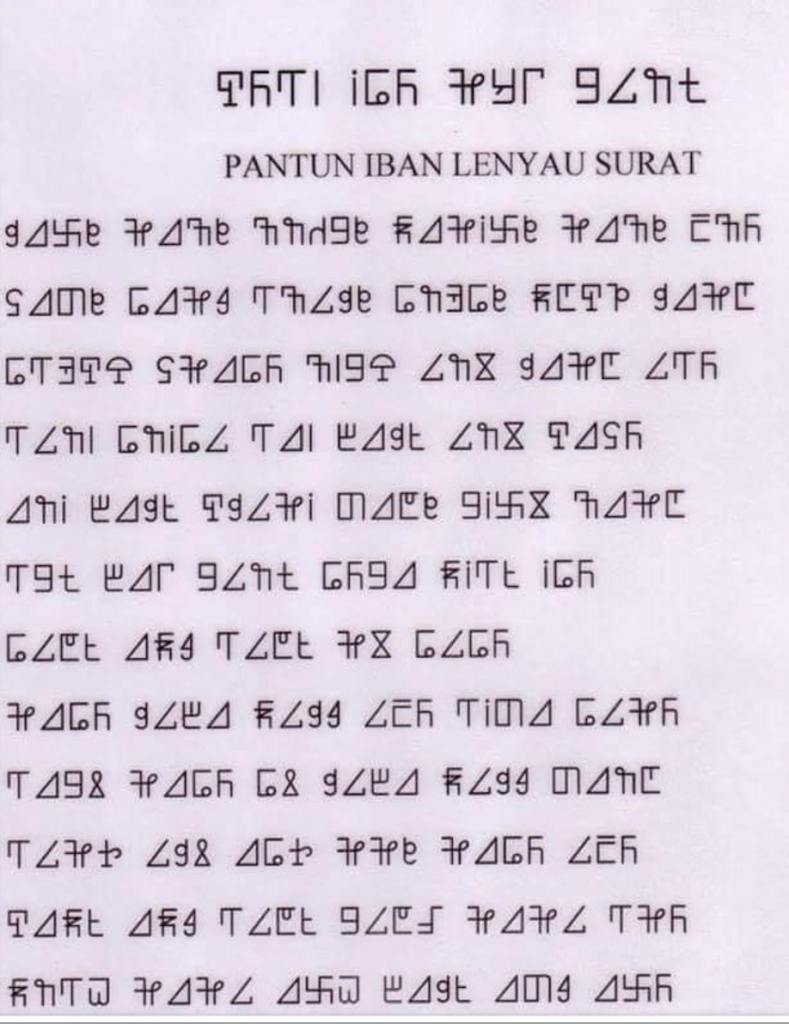

The threads come together: One writing-creation/writing-loss/writing-rediscovery (hereafter WCWLWR) tradition that Piers didn’t mention shows up in Iban tradition, in a poem written by Dunging Gunggu, translated here by Dr. Philip himself. The poem incorporates several motifs found in other WCWLWR narratives, including a flood, extended suffering by the culture, writing being swallowed (sometimes in order to protect it), and the hope, often extended over generations or even centuries, that someone will come to rediscover and/or revive it. In this case, Gunggu may be proposing that he himself is the savior, the King Arthur-type figure, who will save his people by giving them back the vital art of writing.

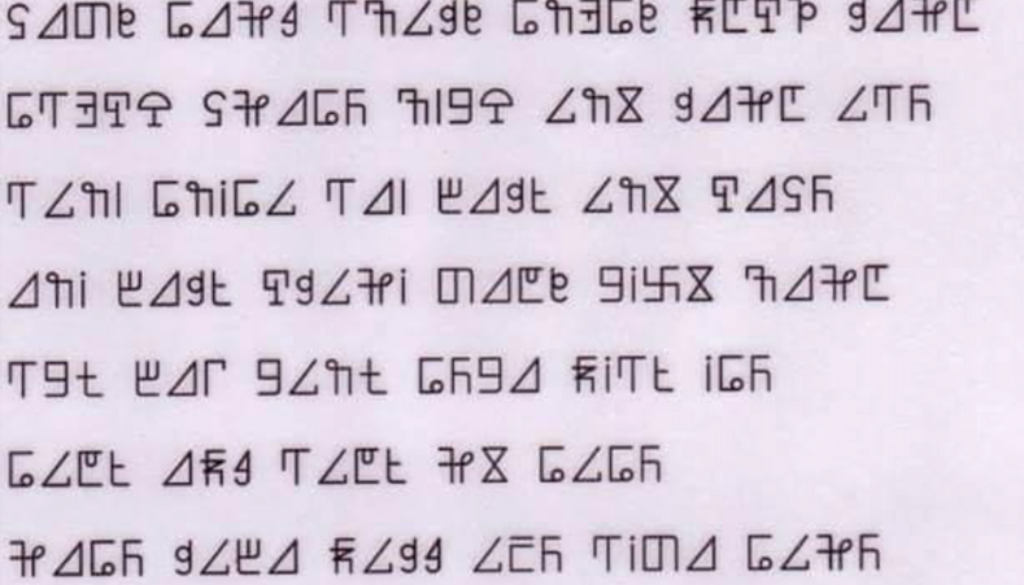

Here’s the poem in the original:

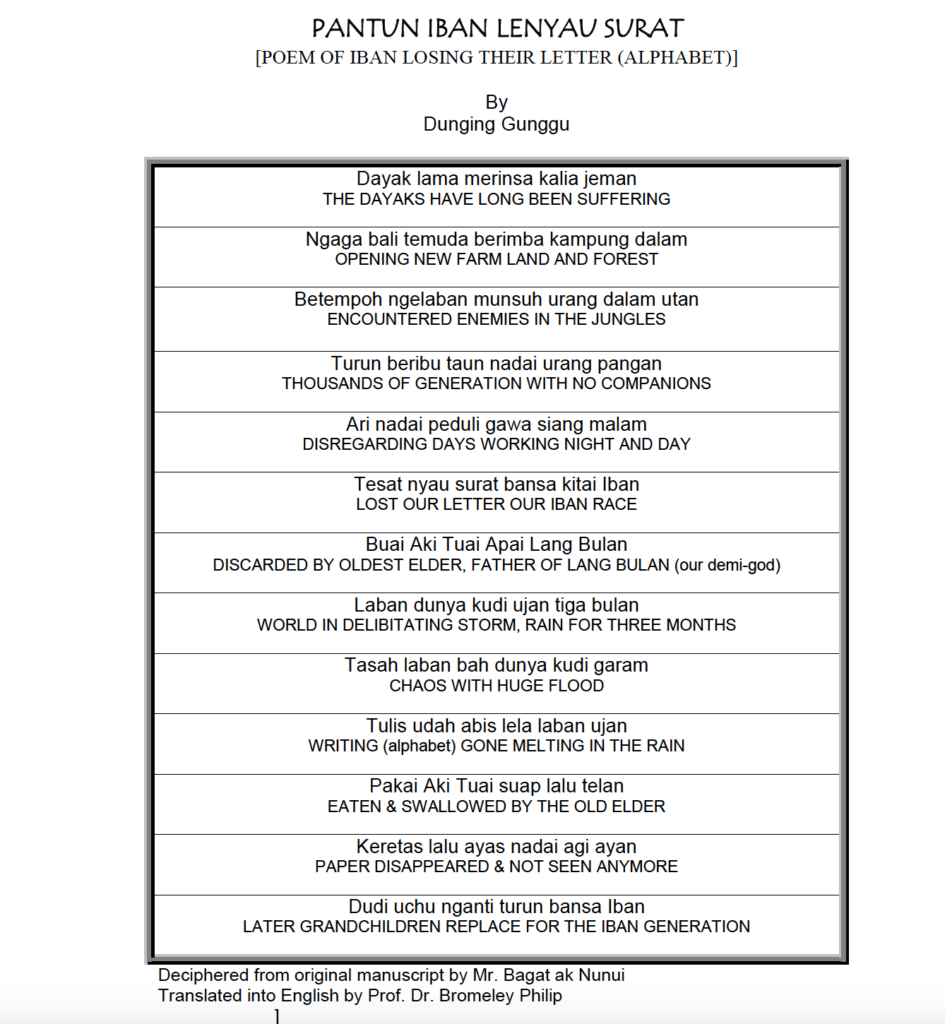

And here it is in translation:

“You don’t know what you’ve got ’till it’s gone,” observed the linguistic anthropologist Joni Mitchell, and these narratives show just how much better those who do not have writing, or their own script, understand the value and importance of writing than we do.

I realized while I was in the shower this morning that writing is like water. Those of us lucky enough to have it in abundance (literally on tap, both hot and cold) are far less able to understand the value of water than those who have bad water or no water at all, who have to walk miles to fetch it from a stream through the dangers of wild animals or–especially as this is often a task assigned to girls–rape and murder.

We in the fortunate West struggle to understand the value and meaning of writing because it is everywhere. In fact, it is everywhere precisely because we once appreciated its value, which we have now forgotten so far that we’re handing it over to machines.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.