Oromo: First and Last

In another blog post, I have written about four people who were killed for having created writing systems for their people. We know of others, though, who have been persecuted for their work and, though not actually assassinated, died as a result of that persecution. One is Sultan Ibrahim Njoya; another is Sheikh Bakri Sapalo.

Many scripts are the work of one person; many scripts never survive the death of their creator. Few scripts are as closely associated with one person as the Oromo script, and few come to such a tragic end.

Sheikh Bakri Sapalo (born Abubakar Garad Usman; November 1895 – 5 April 1980) was an Oromo scholar, poet and religious teacher. The Oromo, one of the largest ethnic groups in Ethiopia, are also one of the oldest peoples inhabiting the Horn of Africa; they may have been living in north Kenya and south-east Ethiopia for more than 7000 years.

Under Haile Selassie’s regime, though, the Oromo language was banned in education, in conversation, and in administrative matters.

As a boy and a young man Abubukar studied under several distinguished Islamic teachers before returning to his home village of Sapalo, where he began to teach religion, geography, history, mathematics, astronomy, Arabic, and the composition of writings in the Oromo language. He also began to compose poetry in the Oromo language, which not only brought him fame but the name he afterwards was known by, Sheikh Bakri Sapalo: “Bakri” is the popular form of “Abubakar”; Sapalo was the name of his village.

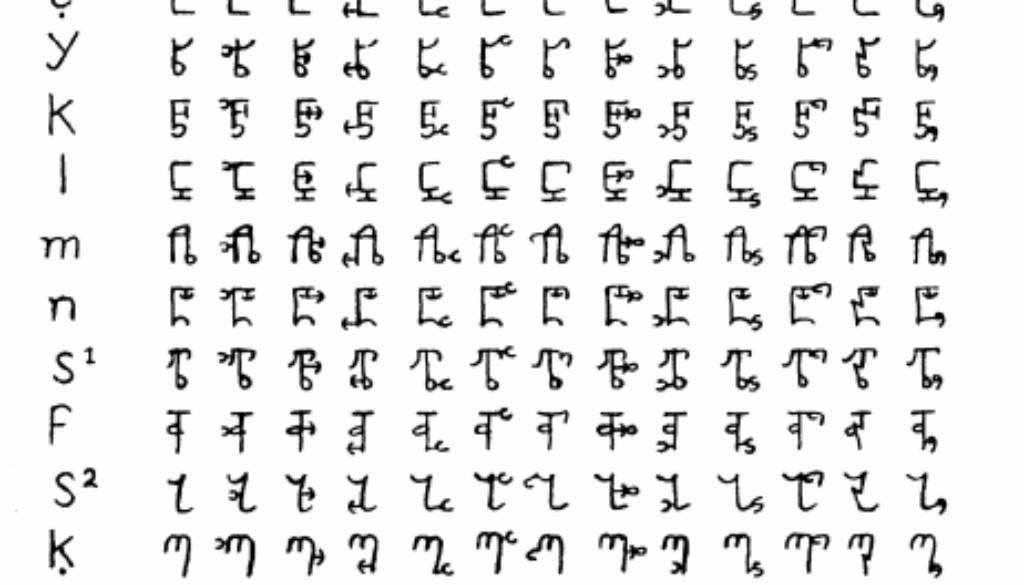

At the time, the Oromo language was almost exclusively oral, occasionally written in either the Latin, Amharic (Ethiopic) or Arabic scripts—hardly adequate forms, as Amharic has only seven vowels, whereas Oromo has ten.

Sheikh Bakri is believed to have invented his writing system for Oromo in 1956 at the village of Hagi Qome, perhaps to keep it secret from the authorities, who would have strenuously opposed Oromo being written in any form, let alone in a script other than Ethiopic.

As is often the case when a marginalized culture develops its own writing system, the Oromo responded to Sheikh Bakri’s script with great enthusiasm, and a number of people in his region began to use it.

As is equally often the case, this surge in self-respect and literacy among the Oromo was viewed with alarm by the Ethiopian authorities and, in the name of national unity, Sheikh Bakri was placed under house arrest in 1965.

He was allowed to continue teaching, though, and over the next few years he wrote Shalda, a twenty-page pamphlet which purported to be a work of religious instruction, but was actually a veiled account of the suffering of the Oromo under Haile Selassie.

R. J. Hayward and Mohammed Hassan note that Shalda is both the first and the last major writing in Shaykh Bakri Sapalo’s alphabet.

In 1978, after Haile Selassie was deposed and the Derg gained power, Sheikh Bakri and his wife fled to a refugee camp in Somalia. Sheikh Bakri had hoped he would be allowed to proceed further to Mogadishu where he could work and have his writings published, but he never received permission to leave, and he died in the camp.

Sheikh Bakri was also a renowned Oromo poet. “Shaykh Bakri, write Hayward and Hassan, “stirred the imagination and captured the love of the Oromo masses by means of his poems, which were composed in their language and were short enough for the people to learn by heart.”

I am entirely indebted to Pete Unseth for bringing this story to my attention.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.