Rovás

This column aims to celebrate and draw attention to people doing original calligraphy and type design in their traditional minority script. In most cases, this act of revitalization is taking place in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Indonesia or Africa, as these are the regions with the greatest number of minority scripts.

Today, though, we’re celebrating someone from one of the least likely regions: Europe. Roland Hüse is a Hungarian designer who is developing new fonts for a script that most people (myself included) tend to assume is extinct: Rovás, or Hungarian Runes.

Traditionally, Rovás (pronounced Rovash) is a name for scripts being used within the Carpathian Basin during the 7th and 10th centuries. The Székely-Hungarian Rovás survived, and is almost exclusively seen, in Transylvania (today, part of Romania), where foreign missionaries used these letterforms for writing Christian prayers and sermons in Hungarian for the Székely people, a community of Hungarians who were border guards and played a role in the defense of the Hungarian Kingdom from the east.

Most surviving Rovás are carved in wood, and nowadays can be seen on folk art products and on doorposts and front gates as a form of blessing, usually carved in a downwards motion using hammer and chisel—hence the predominance of straight lines of a vertical or diagonal alignment.

Rovás were also whittled by shepherds into their crooks or sticks with a knife. The shepherd would “write” down one side of the stick and then back up the other, so in effect the script went both R-L and L-R, though now it is officially R-L, which is how it is used in today’s type design. This also meant there was a tradition of mirroring in writing Rovás, as well as combining the letters together as ligatures due to fitting the text onto often limited surface it was being written on.

Type design in Rovás also faces a series of historical challenges.

In the past thousand years, the script has had to adapt to changes in the Hungarian language, such as borrowing or creating new glyphs (c, é, h, ö, ty, q, x, y,). As Rovás characters represent sound values, there are some glyphs that may stand for two different Latin letters or accented characters. The script was adopted into the Unicode standard in 2015 under the name “Old Hungarian”—a term that caused some controversy, Hüse says, as the term “Old” suggests it is extinct. Moreover, some of characters were left out of the encoding, making it difficult to use for modern Hungarian.

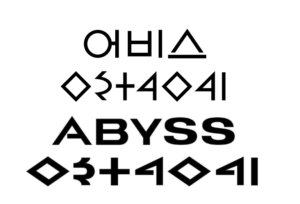

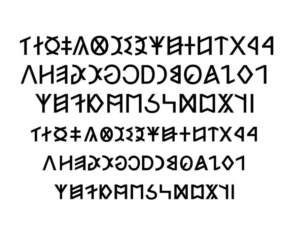

His focus is more on the present and the future than the past. “Nobody wants to learn the way they to spell correctly back then,” he said. “I’m trying to modernize the script, looking for the right way of making it easy to use and adopt for today’s users with various stroke weights, styles, developing new typefaces as well as adding Rovás script extensions to existing fonts such as Roboto, Helvetica etc.”

He’s well aware that in some respects it’s a very simple and angular script, and he has experimented with ligatures and overall composition to add elegance and geometry, studying and drawing inspirations from Japanese and Thai lettering traditions and styles.

He’s also asking some interesting hypothetical design questions. Rovás was never an official writing system—what if it had been? What if at some point it had been written in ink? With a calligraphy pen? What if it had been cast in type and printed? How would these circumstances have affected the look and feel of these runic looking letterforms?

Rovás, he says, is gaining popularity among Hungarian speaking population worldwide and symbolizes an emotional and cultural bond to their motherland.

But for the Székelys, Rovás has another association—it’s a reminder that there were times they were pressured into being and speaking Romanian—a form of coercion that, he says, still occurs to this day.

Roland Hüse’s work can be seen at https://www.instagram.com/rolandhusedesign/.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.