Goulsse: The Vanderbilt-Burkina Faso Connection

Few things make my work more delightful than the discovery of a new individual or group working on reviving their culture through its alphabet, or the discovery of an entirely new (to me) script.

What better, then, than an email out of the blue that offers both?

The script has three qualities that are found much more frequently in newly-created African scripts than those from elsewhere in the world: it is based on graphic elements from local cultures; as a result, the letterforms have their own design style rather than being reminiscent of Latin or Arabic scripts; and it is designed with the ambition to be used for multiple languages as part of a post-colonial, pan-African cultural rediscovery.

It also has a quality that can be seen as a much more recent development: it was invented not in its homelands, but in the diaspora—specifically, by a coalition of young Africans studying in the United States.

The other thoroughly modern aspect of the script is that it began not as a writing system but as an app.

Wenitte Apiou, a student of electrical engineering and mathematics at the Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, was born in Burkina Faso but moved to America when he was five.

Growing up, Apiou’s family only spoke French—Burkina Faso’s official language—and some English in the household. His parents are from two different ethnic groups: his mother speaks Mòoré, the most spoken indigenous language in Burkina Faso, and his father speaks Kasem, a minority language spoken by about 100,000 people in southern Burkina Faso and Northern Ghana.

“The only language I’m fluent in besides English is French, which makes it difficult to communicate with some of my older family members who never went to school and were not able to learn French fluently,” Apiou recently said in an interview. He decided to try to build a language app that would connect speakers of minority West African languages.

He shared the idea with Boluwaji Odufuwa, who was studying computer science at Harvard. Odufuwa was born in Nigeria but also moved to America in his early childhood, and understood the problem Apiou was trying to solve. The two began work on a learning-by-gaming app they called Mandla, a Zulu and Xhosa word that means power.

In the summer of 2021 Apiou was in Burkina Faso, searching for someone who could help him make reliable Kassena translations and audio recordings for the app, when he was introduced to Babaguioue Micareme Akouabou.

“So we have worked together since then to create Kassena translations and audio recordings to teach the language on the Mandla App, and then had the idea to create a modern script.”

They decided to base the script on the logographic writing system of the Kassena people of Western Africa, in use since at least the 16th century—and to draw on community help and involvement.

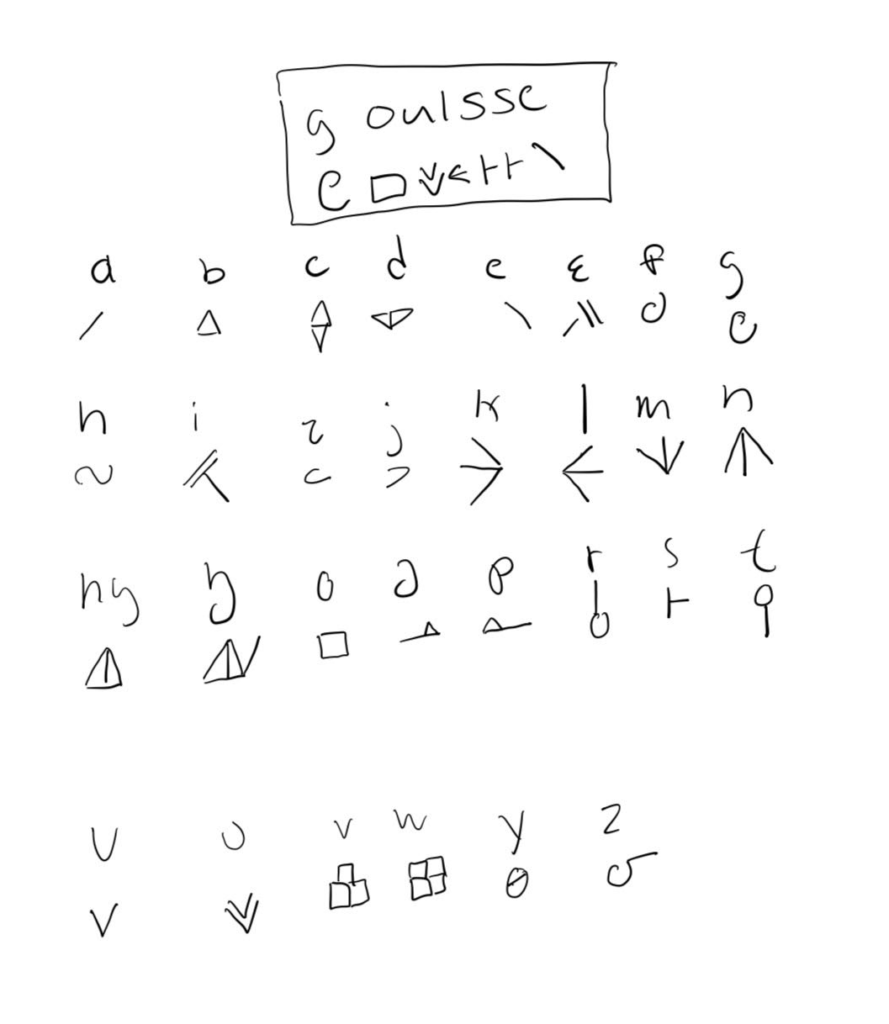

“The Kassena are well known for the logograms on their houses, symbols representing concepts such as wealth, love, peace, devotion to God, and prosperity. The letterforms were decided upon by a process involving citizens of the city of Po, in Burkina Faso (mostly high school and university students) whereby multiple versions of characters were proposed and the groups voted upon which ones to include.

“We also had the guidance of one of the members of the Kassena language council, Fernand Ki, who was also one of the first people to train people to read in the language.”

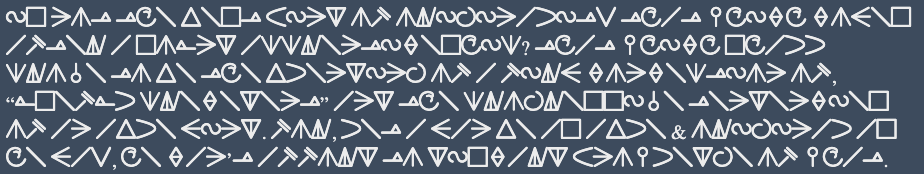

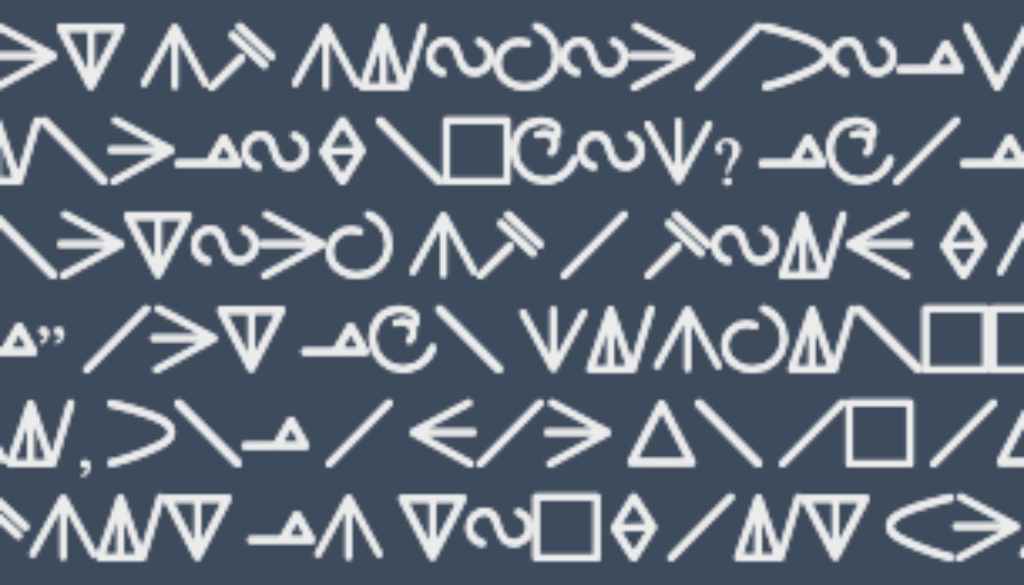

The result was a highly geometrical-looking alphabet with 30 letters called Gʋlse (anglicized as Goulsse), meaning “writing” in Mooré. Gʋlse is written from left to right, has no uppercase or lowercase, and uses the standard international Hindu-Arabic numerals.

The script is being taught to write the Kassem language in Po, Burkina Faso, Apiou reports. There are also plans to teach it in Ouagadougou to write the Mooré language.

“Currently we are working on building an online open-source crowd-sourced dictionary for African languages. It features definitions, etymology, and example sentences written in the native language using both indigenous scripts and Latin script, as well as parallel definitions written in English and French as well as provide tools for typing African languages in native scripts on the web.”

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.

February 26, 2023 @ 7:26 pm

I’m 21 years old from America but I’m ethnically Kassena! I understand it more than I speak but I do speak a decent amount. It’s hard trying to relearn a language that such a minority but I always search for Kassena resources on the internet. I always excited when I find it so I want you to know that someone is rooting for you to bring attention to the Kasem language!!