The Right to Speak: Osage

Our just-launched Kickstarter campaign aims to create a large public sculpture that says, in English and three different endangered alphabets, “The Right to Speak, the Right to Read, the Right to Write.”

Language, spoken and written, is a human rights issue, a social justice issue–and each of the three scripts tells its own story of how true this is.

Like many Native peoples, the Osage suffered subjugation and forced resettlement from Missouri, Arkansas and Kansas to Oklahoma. Osage children born after 1906 were sent off to boarding schools, where they were forced to speak English. Nobody knows just what other horrors they suffered in the name of cultural assimilation.

Not surprisingly, by 1950 most Osages spoke English as their first language.

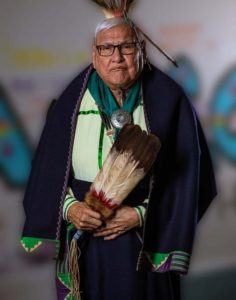

Herman Mongrain “Mogri” Lookout started trying to learn his native Osage in 1971, when he was 32, but by the end of the twentieth century there were perhaps only two dozen elderly speakers left. His uncle told him, “Don’t learn Osage. It’s dead. let it go. Go learn Spanish or French, something that’s going to do you some good.”

Yet he decided to commit to Osage. He could pray in Osage, as he had done so with his father, and with some effort he could pick up conversational Osage. The problem was, the Latin alphabet didn’t fit the sounds of Osage. Trying to spell phonetically just caused chaos.

So he began to invent an Osage script. He chose each letter to look a little like a Latin letter so the new forms wouldn’t seem strange and difficult, but each had a unique Osage sound. In 2004 the Council of the Osage Nation passed a resolution initiating the Osage Language Program. After many years of work, the Osage script was finished and digitized, and is now available in an Android-friendly font.

The new script, then, played a part in reviving the language. Weekly online Osage languages classes are currently offered at beginner and intermediate levels, and over a thousand students are enrolled.

But the new script also contributed to a revival of Osage pride.

“I think the most important thing about creating an orthography,” said Warren Queton, Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma Language Advocate, “is reclaiming your own identity as people, in terms of the sovereignty of your nation.

“To have an orthography,” he said, “is one more tool to say, as Osage people, `This is who we are. This is our identity. This is our language. We made this. We accepted it. We reclaimed it. Now we’re going to carry it on to the future.”

Despite Lookout’s remarkable work and the continuing efforts of the Osage Language Program, few people can read or even recognize the Osage alphabet. The purpose of our sculpture is to make the invisible visible—to bring Osage into the public eye, to tell its story, to add momentum to its revival.

Please support our campaign. We can’t do it without you.

Thanks.