Giving Me Wings: The Argument for New Scripts

At this very moment, someone is working to create a new, unique script for their culture and their language.

We know of more than 125 scripts that were created by individuals on behalf of their people, most of which have struggled to gain acceptance and wide and prolonged usage, and for that reason they are often dismissed as the work of cranks or, equally damning, “enthusiasts.”

That’s an outsider’s view, though. Let’s look from the inside.

Creating a workable and learnable script for one’s language presents a whole range of linguistic challenges, of course, but in many ways that’s the easy part. Designing and assigning symbols may take a year or more; getting the script accepted, adopted, and taught can take decades.

Resistance comes from a range of directions, some of them surprising. Given that the culture in question is almost certain to be a minority or indigenous group, national governments often view script creators as troublemakers, and their efforts as “political.” (We know of several script creators who have been arrested and even, in four cases, killed.) Funding is almost invariably zero, so the script author likely has to become teacher and even publisher, and as no typefaces will exist, all publications will have to be written by hand.

In all this kerfuffle, the voices least likely to be heard are those of people whose lives were improved, even transformed, by the new script. I was fortunate enough to have been contacted by Lily Adlam, who in a series of emails expressed how and why her own life, and those of many others, have been changed by the invention of the Adlam script by the brothers Ibrahima and Abdoulaye Barry in 1989. Here is her testimony.

Her last sentence, by the way, refers to the fact that Adlam is an acrostic of the first four letters of the alphabet (A, D, L, M) which represent the phrase Alkule Dandaydhe Leñol Mulugol: “the alphabet which protects the people from vanishing.”

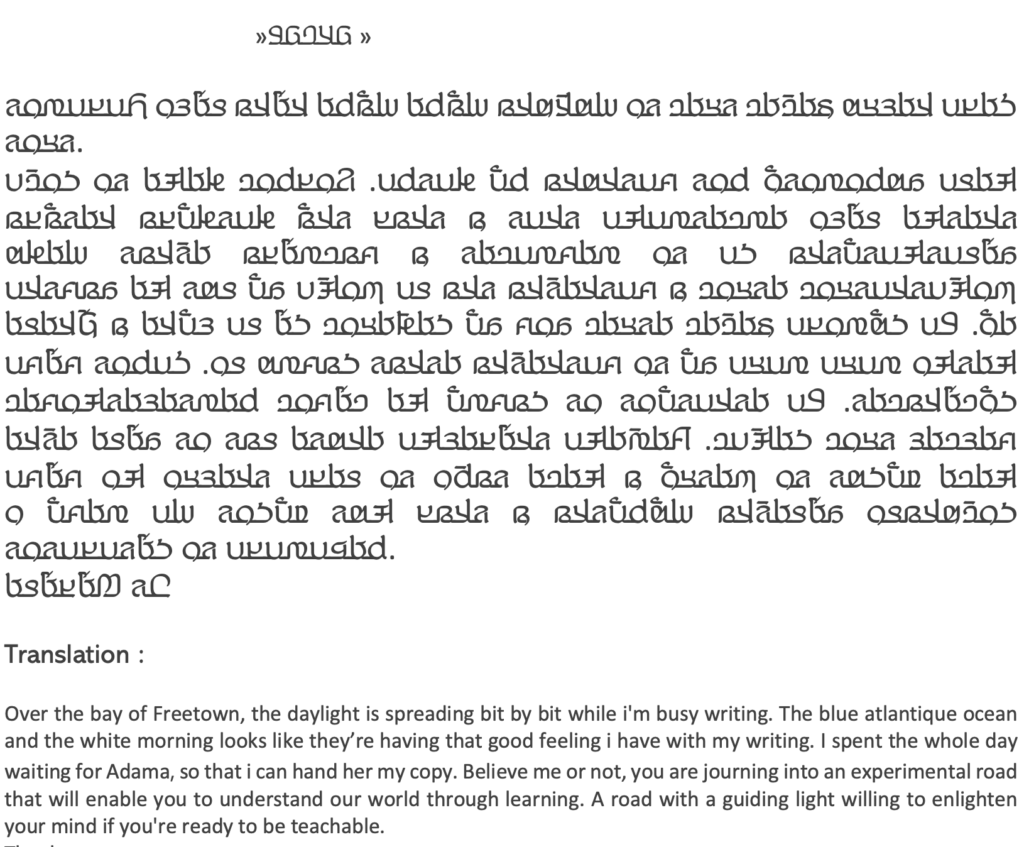

My name is Lilly Aissatou Adlam. I am from Sierra Leone.

During my youth, in Sierra Leone, I used to speak with my neighbors and friends in Krio and English most of the time. At that time, Fula was written with the Latin and the Arabic letters. And during those days, writing was not in the “woman’s land.” So I grew culturally as well as academically without speaking Fula properly and without writing it at all. When I arrived in France, I switched to French, so I lost my language and failed to pass it to my children. I learnt less about myself, making me somehow a poor person.

When I first saw our script (November 2019) I was in a meeting given by the Adlam team. Not knowing whether I would join the team, I bought one of their books. I went home happy and proud to have in my hand a book written in my language with our own script. But the journey with my book didn’t start right away because my apprehension of the letters made me [hold back] for months.

In May 2020, I was told that our script has its keyboard on computers and phones. That’s how I came to gain confidence in myself and started the journey with Adlam.

Since last June, I’ve been studying the Fula grammar on the internet with other Fula students. Our teacher is Ibrahim Barry, one of the creators of our script. Through this studying, I have realised that my language is unknown to me. Even though it is my mother’s tongue, many words were hidden from me, some became uncertain, some became familiar. New ones came in, shaping and sharpening my brain every day, changing my way of conversing in Fula.

From that time, until now, I have been writing a lot on Facebook on various topics. Also, every second Saturday of the month, I hold a class for new learners of our script in one of the libraries in my town. Moreover, I have students on the Whatsapp and Telegram apps. I also joined the Fula committee in September 2020 for the development of our culture, language and Adlam, and became the speaker of the group in January 2021.

After being selected by Professor Ibrahim Barry to join the first class of students that will teach Fula language to Fulas and other people, in the future, I started to be more concerned about my handwriting and its improvement. I also engaged myself in spreading the information about our script on radio, events, to friends and colleagues.

Adlam is giving me wings. My family, the walls of my place are all journeying with me now. The more I proceed to go forward, the more I find binds holding me tight to Adlam and to my culture. I am eager to teach our script, one day, somewhere in Africa or in America.

Reading in Fula, writing in Fula is like quenching my thirst under a hot sun. Adlam is the water (script) that saved me (my people) from vanishing.

She added this postscript, in the Fula language and the Adlam script:

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Rosetta, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labour.

The Argument(s) Against the “Tree of Life” Paradigm for Script Evolution – Endangered Alphabets

March 16, 2022 @ 12:33 am

[…] overturn the notion that the colonial script is the gateway to literacy. Lilly Aissatou Adlam recently told me that the newly-created Adlam script had utterly transformed her life, as it has transformed the […]