Designing New Scripts: The Missing Mro

By my calculations, at least a hundred new scripts have been created in the past century. I’m not talking about scripts created for private use, or for use in fiction, film, or television, but scripts intended to give practical visual identity to a language that had previously been using a script imported from, or imposed by, another culture.

This is not only an arduous task, but a hazardous one. At least four people have been killed for creative original indigenous scripts (see my blog post on the subject) and many others have been harassed or imprisoned. All the more reason for recognizing those who make the effort, and take the risk.

This month’s post recounts the story of one of the most mysterious script creators, a young man who invented and taught a religious script for the Mro people of Bangladesh and northeast India–and then disappeared.

The highlands of northern Southeast Asia, sometimes referred to as the region of Zomia, have long been an area of refuge for minority cultures fleeing ahead of armies or persecuting neighbors. Its inaccessible valleys, forests, and uneven topography—plus the fact that, in conventional terms, this is land of little value to larger and more powerful forces who are more likely to occupy fertile lowlands and river valleys—has meant that a number of peoples such as the Chin, the Hmong, and the Karen have made their homes in Zomia as best they could.

From the Endangered Alphabets Project’s viewpoint, one especially interesting aspect of this history has been the repeated creation of small-scale, highly-local, messianic religions that created and used their own scripts, which had not only a linguistic purpose but were directly involved in the practice of religion and the development of social organization. In several cases, these religious movements were led by individuals who died or were killed for their activism. Surprisingly often, their communities have since maintained a millenarian belief in their eventual return. One of the least-known and least-numerous of these language communities is the Mro.

The Mro, or Mru, have lived for centuries in the uplands on both sides of what is now the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. They have a recently-created script generally referred to as Mro, also called Crama or Krama, after the religion founded by the same charismatic who created the script: Menley Mro.

Almost nothing is known about Menley Mro outside the Mro community, which is why I was startled and delighted to be contacted by Fungpre Mro—Menley Mro’s nephew.

I asked him to tell me about his uncle, whose mystery is enriched by the fact that, after founding an alphabet and a religion, he vanished, and has not been seen for more than 35 years.

Fungpre Mro’s account has been edited for spelling and clarity.

A short introduction to KRAMA

By Fungpre Mro, the nephew of Menley Mro

Menley Mro was born in 1965 into a poor Mro family in a village called Kretkung in the Bandarban District of Bangladesh. His father’s name was Mansing Mro; his mother was Tumtey Mro. His father named him Menley, but in time people came to know him as Kramadi. The word Kramadi is closely associated with the name Krama, a word meaning “possessing infinite knowledge.”

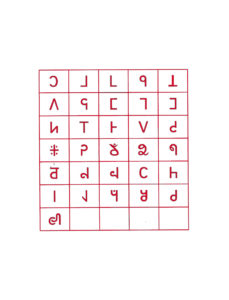

In 1980, at the age of 15, he got admitted to a Mro residential school. In 1981 he started to create a Mro script, and after one year he had completed it. During the next year he started to write poems and songs—the first in the Mro language to be written in the new script, and in 1984 he published the script for the Mro people.

Until that time, most of the village schools taught in the Marma alphabet [a close cousin of the Burmese alphabet used by the Marma, another ethnic minority group of the region]. The ignorance and superstition of the Mro society starts from there. In 1980, the Mro Residential School in Sualkar, Bandarban was established. Meditation begins here with studies and daily work. Every night, the teenager Menley meditated under the ashwattha tree near the school. He searched god for the key to liberation. He did not have to wait for a long time.

In 1982, his alphabet was reported in the school. The teachers were surprised. Menley didn’t stay in school for long after that. He returned to the village, but continued his meditation and alphabet teaching. At first, people thought he was crazy. Only one village elder, Langpung, believed in him.

It was a miracle in itself that Langpung became a believer. One day, he went to cut bamboo in the forest. Suddenly, a man in white spoke.

“O Langpung, sharpen your hands for the right thing to do. Summer fire cannot be stopped; It is not possible to stop the Krama dharma and its alphabet. But if you don’t believe, this alphabet and religion will be lost.”

Langpung was a man of statue in the village, so not everyone could dismiss his words. Arrangements were made to learn the Mro alphabet in the village, with the sangmi, or teacher, charging no fee. He called for a grand conference on a Sunday in April to discuss the alphabet and language of all. This can be compared to the Mahasammelan of Buddhism and the Council of Christianity. It was from this day that the Kramadharma (Krama religion) officially began to spread–not just in Bangladesh, but in Myanmar too.

The name of the religious book of the Kramad is Riung Khati. It is also recorded in their religious customs and rules of life. The Krama directive shows the decentralizing of power according to social action. Each village is led by six gurus, in whom some separate responsibilities are entrusted. It is the responsibility of the Chakhang Uup to provide herbal treatment, justice and legal advice are headed by the Arip Uup. It is up to the Ori Uup to make a law for the villagers, the Sangmi Uup for the education of the children of the village, and the Prasar Uup for the interpretation and promotion of religious issues.

The Kiong (Church) or Bihar is the holiest place in the Kramadharma, and is divided into three parts. The Soluk Kim (chapel or prayer room) is the main place to pray in Bihar. The most sacred part has to be washed before entering. The Soluk Kim is again divided into two parts. One part is of the Orissa and the other is of the pilgrims. However, there are rules for the seating of the pilgrims: men and women are different, married are in front and singles are behind. The pilgrims are called fifteen times by ringing the bell. The inner fasting ritual also has its own speciality.

Phung or charitra rituals are important elements in Kramadharma. Eight phungs are essential for the practice of worldly religion, in addition to refraining from alcohol and other drugs: theft, robbery, lying, gambling, killing, greed, violence, and bad eyeing of people are forbidden, not unlike the Ten Commandments of the Bible or the Ashtammarg of Buddha.

Two more phungs have to be performed for the family or monks–to be out of all human relationships and to treat God as the only relative–as well as to go to the forest and do penance.

For a short time, Kramadi Menley travelled to many places to promote religion and alphabets, but in July 1984, he chose to leave his own society when he was only 19 years old to practice a more rigorous meditation. When he left, he just told the people that “I’ll be back after filled my austerities. It can take a minimum of 15 years.”

According to the prophecy, one day he will appear in the world with a new religion called Usekshati Maanglong.

Following up by email, I asked: “So you have no idea what happened to him, or where he is now?”

“Basically it’s so hard to say where he is now,” Fungpre responded, “because no one knows where he was going when he left us.

“He gave a speech before left, giving lots of information to the Mro community. And Mro people still listen to the recording of his speech when when they get tired on physical work or emotions.”

–Tim Brookes

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque and Rosetta.