Two emerging alphabets

It is still remarkably rare for scholars to get involved in creating and promoting new writing systems, so it seems all the more worthwhile to pass along to you an article by Stephen Morey, an Australian scholar and expert in the Tai languages and scripts of South China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. And as this also gives me a chance to tell you about Ogmios, the wonderful journal of the Foundation for Endangered Languages where Stephen’s article has just appeared, this post represents a win-win-win.

The question “Why create a new script?” is addressed by Stephen in his article; a more detailed exploration formed the basis for one of my Open House talks, which can be seen HERE. Stephen focusses more on an allied question, and a very significant challenge: how do you create symbols that represent the sounds of speech? This issue is repeated all over the world where Europeans have attempted to use/adapt the Latin alphabet, with widely varying degrees of success, for spoken languages that employ sounds that go far beyond standard European speech. Now read on…..

Two Scripts for Languages in Northeast India

While many communities are grappling with the challenges of reducing their languages to writing using already developed scripts such as the Roman script, some people are finding that already existing scripts are unable to fully express their language properly, and so are creating new scripts.

Mr. Lakhum Yogka Mossang and Mr Banwang Losu are two such creators, using their deep native speaker intuitions to create scripts that express all the contrastive sounds of their languages, consonants, vowels and tones.

Lakhum Yogka Mossang, of Namphai Nong, Miao, Arunachal Pradesh, has created a script for writing the Tangsa languages (those included under ISO639:3 nst) spoken in Arunachal Pradesh, India and across the border in the north of Sagaing Region, Myanmar. It is an alphabetic script, genetically unrelated to existing scripts. Although revised several times, the 2020 January version consists of 89 characters: 79 letters (48 listed as vowels and 31 listed as consonants) and 10 digits.

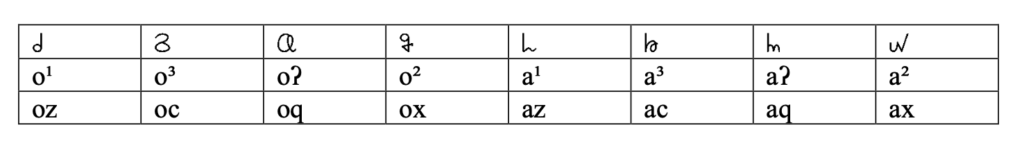

A key design feature of the script is that for each vowel there are four symbols, corresponding to four different tones in Tangsa languages. Lakhum Mossang’s native variety is Mossang, spelled Muixshaungx in a Roman orthography developed by Rev. Gam Win, and /mɯ2ʃauŋ2/ in an phonemic transcription, where both the -x and the superscript number 2 indicate a mid-high falling tone. We usually spell the language name as Muishaung in English, without the -x tone marks. Muishaung has four tone categories: a low falling tone (tone 1), a mid-high falling tone (tone 2), a high possible rising tone (tone 3) and a short or stopped tone.

In Lakhum Mossang‘s script, these are written differently in combination with vowels, as shown in the example below (with the script in the first line, a phonemic rendition in the second, and the Roman based orthography devised by Rev. Gam Win in the third).

Together with Mr. Wanglung Mossang, a native speaker of Muishaung working to preserve his unique language, we’ve recently started making videos to teach the script. The first of these can be viewed on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oBtKTFcr05I. This video, produced during COVID-19 lockdown, was first made as a PowerPoint presentation by me in Australia, and then sent to Wanglung as a video for him to record the pronunciations. These he sent back (via Facebook) and I aligned the sound with the movie! We are also currently working together on an application to include the Wancho script in Unicode.

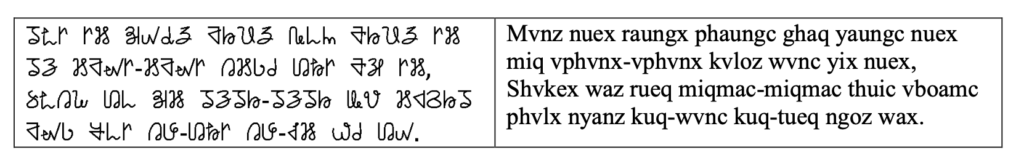

Here is small sample of the script (with the Romanization), telling the traditional story of the loss of writing – God handed out writing to every community, but the Tangsa were among the last and it was given to them on animal skin. They got hungry and ate it, and writing was lost. Now it is found again:

Banwang Losu’s language, Wancho, is related to the Tangsa – both being members of the Tibeto- Burman language family, and both belonging to the group called Northern Naga. Like Tangsa, Wancho has three tones and stop final words. Banwang’s script was created around 2010. I first met him in 2013 when he came down from the remote mountain area of his home village – Kamhua Noknu – to meet me at the market at Moran, in Assam, and join me on a car journey to Digboi, so that we could discuss his script. We’ve been lucky to meet up several times since then and in December 2019 it was a particular highlight that Banwang could attend the FEL conference in Sydney.

Banwang’s script has been accepted in Unicode, which means you can type it right now on Facebook, mobile phone &c. I first came to know Banwang because of a wonderful animated movie that he had created of his script, which was last year reported on the news in India – and you can see it at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=498952827571211.

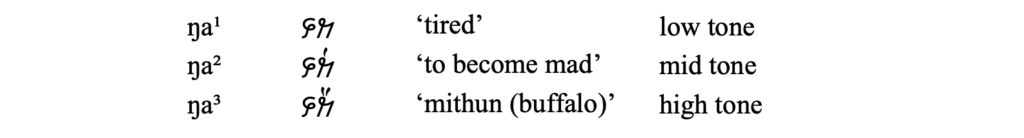

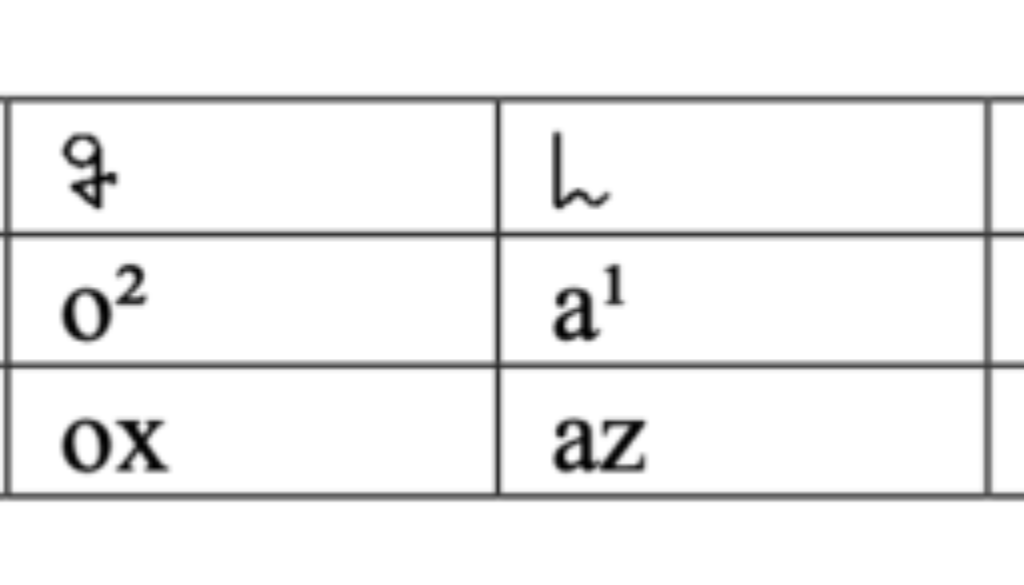

The script marks the tones by no mark – low tone, a single ‘feather’ – mid tone or a double feather – high tone, as we see here:

The full animated video of Banwang teaching his script can be found at

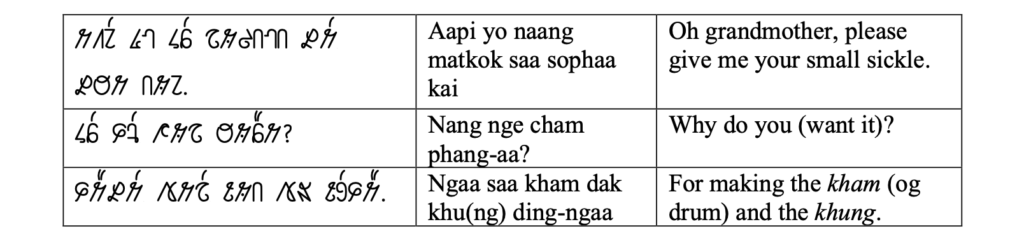

Here is a small sample of a script with a children’s song, sung by the late Soipho Pansa; here we see the script, a ‘simplified’ Romanization with tone marking, and an English translation:

— All materials copyright Stephen Morey 2020

August 20, 2020 @ 10:43 am

Beautiful. I have done a script for an African language. Is there any way a keyboard can be made to enhance my project? I’m doing it all on my own. I believe, with the keyboard, I can build a quick dictionary and grammatical aspect of the language. You’re doing a wonderful job.

August 20, 2020 @ 3:27 pm

Please contact me at tim@endangeredalphabets.com and tell me more!