Another Script Author Murdered

Creating an alphabet may seem like a harmless pastime, and author-designers inventing conscripts for science fiction/alternative-reality novels or television series are probably only at risk of eyestrain and carpal tunnel syndrome.

As soon as writing has a political or religious purpose, though, things change. It’s a sign of how powerful a force writing can be in creating a sense of community and identity that at least four people have been murdered for creating a writing system for their people.

Late in the ninth century, King Sirijonga Hang of Yangwarok kingdom rose to power, subduing all the independent rulers and taking over as the new supreme ruler of Limbuwan. He built two big forts, one of which still stands. According to tradition he was responsible for another construction that stood the test of time, and unified all ten Limbus: the Kirat-Sirijonga script.

According to Limbu folklore, he prayed to the goddess Saraswati for wisdom as to how to devise a script for his people, and in response she revealed the story of creation to him, written in the script.

The mythic or archetypical quality of this story is reinforced by the fact that, having apparently done its job, the script vanished. But its disappearance seems to have had an Arthurian waiting-to-return quality, for some 800 years later, during a time of tension and upheaval in Sikkim — in other words, just when it was needed — it was reintroduced by the Limbu scholar Te-ongsi Sirijonga (believed to be the reincarnation of King Sirijonga), in the early to mid-eighteenth century.

He researched, revived and taught the Kirat-Sirijonga script, collecting, copying and composing Limbu literature, teaching Limbu language and the importance of Limbu history and cultural traditions while at the same time preaching openness to other cultures and knowledge.

This work made him a cultural hero, but cultural heroes are also often threats. The Sikkimese Bhutia rulers ordered that he be tied to a tree and shot to death with arrows — possibly a cruel irony, as limbu means “archer.”

The first prophet to bring writing back to the Hmong was the rebel Pa Chay Vue who, in 1918, led a revolt against French rule in Laos during the Guerre du Fou, or War of the Insane. Pa Chay asserted himself as the Hmong equivalent of King Arthur, the leader who had returned from death and history to save his country. He claimed he had visited heaven, where he met four madmen who knew how to write and with whom he communicated by means of a single letter. It was this writing system, written with natural ink on processed bamboo bark and expanded to include other glyphs, that he later used to urge Hmong to rise up and join his movement. Pa Chay also distributed squares of cloth inscribed with his script as amulets for protection in battle. Despite this protection, Pa Chay Vue was assassinated in 1921.

Three years later, the French army in Indochina began to intercept insurgent correspondence coming from southern Laos and circulating as far as Vietnam and Cambodia. What distinguished these particular messages, over thousands of kilometres of upland terrain, was the unusual Khom script in which they were written.

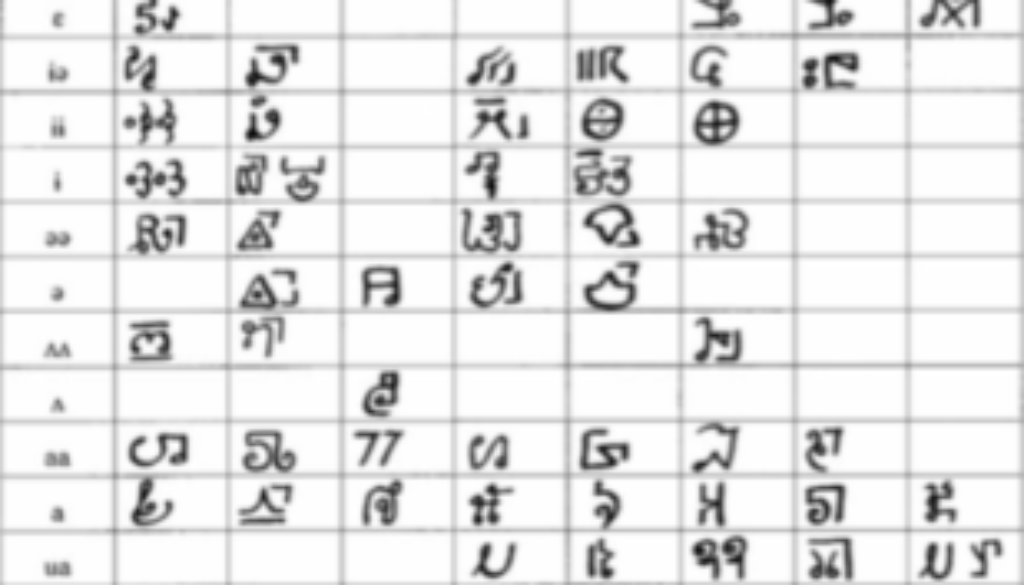

Its creator was Ong Kommadam, one of perhaps a hundred self-styled messiahs who led rebellions against the French colonial state in the early twentieth century. His was another “revealed” or trace script. According to Hmong story, he would repeat a sound and again and again until its corresponding symbol manifested itself on the bare skin of his chest—at which point a scribe would copy it down and wait for the next one. This became the Khom script (see graphic).

Kommadam developed an aura of invulnerability, especially after he survived an assassination attempt when a French official, claiming to have been sent for peaceful negotiations, shot him in the chest with a pistol hidden in his pith helmet. This was too much for the French, who eventually mounted a land-air operation that used both bombers and elephants, in which Kommadam was killed. The French authorities collected and destroyed every document in his script they could find.

Like Arthur, though, his legend, along with his script, lived on. According to one Hmong narrative, his sons transcribed the characters from his tattooed back before he was buried; in another version a man who may have been the immortal Kommadam had himself tattooed with the script, escaped to the Wat Phu temple, and still lives there as a monk.

In 1959, an unlettered Hmong farmer and basket maker named Shong Lue Yang announced that he had been inspired by God in a series of visions to create a written language for the Hmong, and, like Sequoyah, set about converting first himself and then his people from non-literacy to literacy.

John Duffy writes, “The writing system presented the Hmong with a conception of themselves as united, sovereign, and spiritually redeemed,” John Duffy wrote in Writing from These Roots: Literacy in a Hmong-American Community. “[It] was more than a writing system for its users; it was, in addition, a guide to moral life and religious salvation.”

The effect of his invention was rapid and radical. Almost at once he took on a messianic status for the Hmong: his followers called him “Mother of Writing,” and looked to him for ethical and religious teaching and advice.

At the time he was living in Vietnam, and the nationalist feelings he was stirring up in the Hmong minority made the government uneasy. His supporters helped him avoid arrest, and smuggled him into Laos, but the complex and interrelated wars throughout the region and the outsider status of the Hmong meant that wherever he went, he was accused by both sides of aiding the other. Besides, no government in the region had any sympathy for a nationalist Hmong movement.

By 1971, his religious and cultural influence among the Hmong had grown simply too strong for the Laotian government’s liking, and soldiers were sent to assassinate him.

In more than 50 cases around the world, we know the names of the people who created writing systems. South America represents one of the few cases where we know the name of the person who destroyed them.

As part of his campaign to eradicate pagan rites, Bishop Diego de Landa (12 November 1524 – 29 April 1579) ordered an Inquisition in Mani, ending with an auto de fé in 1562. A large number of Maya codices and approximately 5000 Maya cult images were burned. Only three pre-Columbian books of Maya hieroglyphics and, perhaps, fragments of a fourth are known to have survived.

The Mayan writing system was functionally extinct within fifty years.

This destruction, by the way, was part of an operation in which large numbers of Maya nobles and commoners were tortured by hoisting: a victim’s hands were bound and looped over an extended line that was then raised until the victim’s entire body was suspended in the air. Often, stone weights were added to the ankles or lashes applied to the back during interrogation.

This despite the fact that the Spanish crown had previously exempted indigenous peoples from the authority of the Inquisition, on the grounds that their understanding of Christianity was “too childish” for them to be held guilty of heresy.

Nobody knows how old the Meitei Mayek script is—estimates range from several hundred years to more than 1,000—but we know exactly when and why it died.

The script was lost to the speakers of the language when Shantidas Gosai, a Hindu missionary, spread Vaishnavism in the region in 1709. Pamheiba, the ruler of the Manipur Kingdom who introduced Hinduism, decreed that Meitei Mayek should be replaced by the Bengali script. Books and documents in Manipuri were burned—such a catastrophic and traumatic event in Manipuri history that even today events and marches are held to commemorate this destruction, which is believed to have occurred on 17th Mera (October) 1729.

Here at least the news is not all grim: after a considerable amount of protest and even destruction of property, the government of Manipur has reinstated the Meetei Mayek script, now often called the Manipuri script, in schools. Most writers have stopped using the Bengali script, while others have rewritten their old books using the traditional alphabet, and one copy of the State Assembly proceedings is recorded in the Manipuri script.

Much of the information in this post came from Piers Kelly’s great article HERE.

Designing New Scripts–an ongoing series – Endangered Alphabets

February 18, 2021 @ 1:51 pm

[…] At least four people have been killed for creative original indigenous scripts (see my blog post HERE), and many others have been harassed or imprisoned. All the more reason for recognizing those who […]

Designing New Scripts: The Missing Mro – Endangered Alphabets

July 20, 2021 @ 8:45 pm

[…] hazardous one. At least four people have been killed for creative original indigenous scripts (see my blog post on the subject) and many others have been harassed or imprisoned. All the more reason for recognizing those who […]

Designing New Scripts: Chisoi – Endangered Alphabets

September 1, 2021 @ 4:08 pm

[…] hazardous one. At least four people have been killed for creative original indigenous scripts (see my blog post on the subject) and many others have been harassed or imprisoned. All the more reason for recognizing those who […]

Giving Me Wings: The Argument for New Scripts – Endangered Alphabets

October 30, 2021 @ 4:10 pm

[…] as “political.” (We know of several script creators who have been arrested and even, in four cases, killed.) Funding is almost invariably zero, so the script author likely has to become teacher and even […]

The Argument(s) Against the “Tree of Life” Paradigm for Script Evolution – Endangered Alphabets

March 13, 2022 @ 10:10 pm

[…] is in danger. Colonial administrators are likely to regard the new script as a threat, and in fact we know of at least four script creators who have been killed for their trouble. Even in post-colonial […]