Ainu: a minority of Northern Japan

A few months ago I was contacted by Ivan Brenes, an English-language instructor at Osaka University, Japan, who told me about a minority culture I’d never heard of: the Ainu.

According to the Ainu Museum website, the word “Ainu” means “human.” Ainu culture flourished in the northern islands of Japan, especially Hokkaido, from about 1400-1700. As the mainland Japanese extended their influence into Hokkaido, though, the Ainu fought a series of rearguard battles, losing every time, until a final defeat in 1789 left the Ainu at the mercy of the Japanese.

What followed was the long-sad story repeated all over the world when one culture is dominated by another. The Ainu were oppressed and exploited, prohibited from practicing their own daily customs, given the status of “aborigines,” and forced to observe and practice Japanese customs. In the early 19th century, the Ainu population dropped from some 26,000 to 17,000 as diseases such as smallpox, measles, cholera, tuberculosis and venereal diseases spread among the population, which also suffered the breakup of families because of forced labor.

As increasing numbers of Japanese colonized Hokkaido from Honshu, overt oppression was replaced by discrimination—a discrimination that continues in various forms to this day.

In the face of this, the Ainu are making efforts to regain their sense of cultural identity by promoting traditional Ainu dances and ceremonies. Ainu language classes are now being held in various parts of Hokkaido.

The Ainu language, Ivan explained, is utterly unrelated to Japanese, although because of contact they have borrowed a few words from each other.

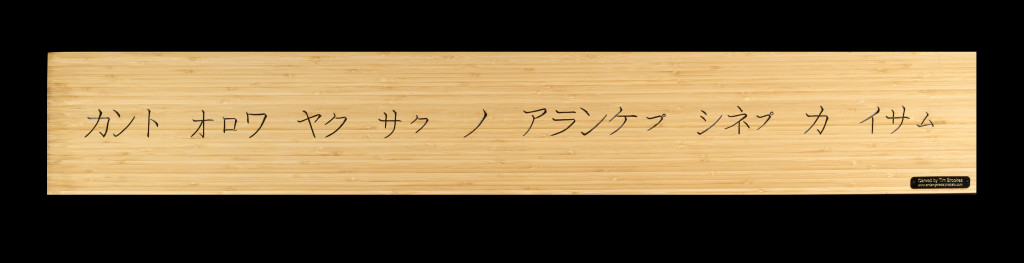

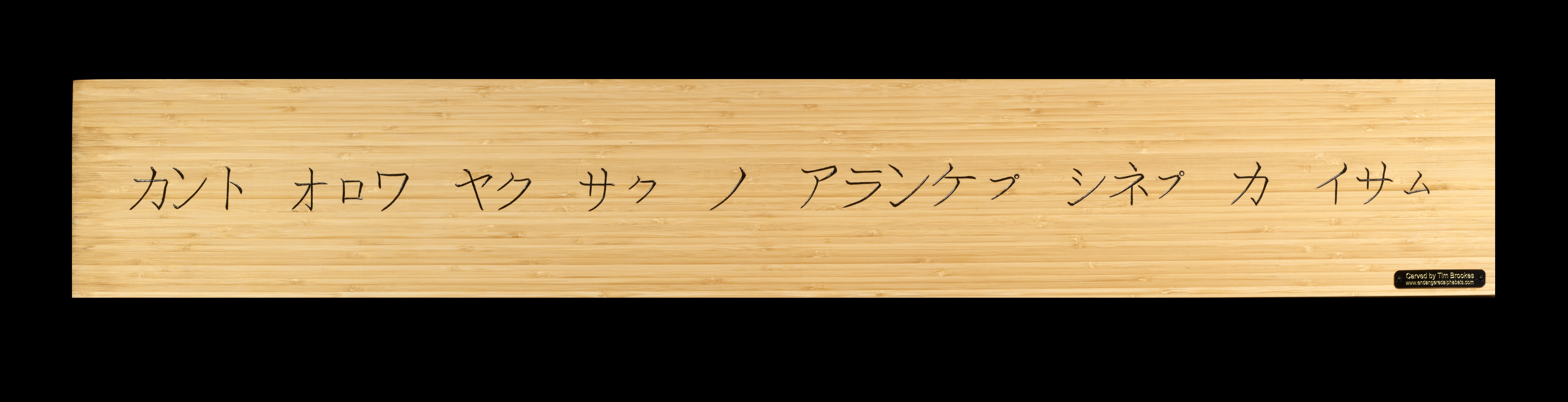

As an oral society, the Ainu never had a writing system, and simply adopted the ones outsiders have used for documenting the language: the Roman alphabet as used by Christian missionaries and Japanese katakana as used by Japanese explorers and researchers.

The Ainu have an endangered alphabet, then, not in the sense that it is different from any other writing system and may die out from lack of use. They have an endangered alphabet in that any writing in their own language is an expression of a culture that has been and remains under siege. To write in it, or to carve writing in it, is an expression of commitment to their culture’s heritage, and a step toward ensuring its survival.

Ivan sent me an Ainu proverb to carve, and the result is at the head of this post. Over the next couple of days I’ll pack it up and send it out to Japan, where Ivan will find the best person to give it to so it can be displayed with pride.

Tim Brookes

P.S. I’m about to do another carving in Ainu on a beautiful piece of bamboo–but it will cost $70. This is why your donations to the Endangered Alphabets Project are so important, and so appreciated.

April 8, 2016 @ 1:37 pm

I visited an Ainu settlement near Hakodate on Hokkaido c. 1998. I appreciate it was a tourist site but it did have the feel of a human zoo. After being funnelled down a hall of souvenirs (a lot of them bear-related) I seem to recall going to an open area where a haggard old man and some young women performed a dance for us tourists. The old man had the distinct look of an Ainu but the girls had obvious Japanese ancestry and would have gone unnoticed in any Japanese suburb. Since my Japanese wasn’t very good I couldn’t understand all the nuances of what was going on but the general dynamic was obvious, and can be seen in marginalised communities the world over.

April 8, 2016 @ 1:43 pm

ps One of the odd things about the Ainu is traditionally they looked similar to whites/Caucasians. They had more body hair than Japanese tend to and pale skins. A lot of Japanese have Ainu ancestry, but it used to be hidden until recently. Interestingly some folk think the old name of Tokyo – Edo is cognate with Ezo another name for the Ainu. Kami – a term used in Shinto a lot and even as a title for the emperor appears to be an Ainu loanword.