Our Golden Hour Part II: Gifts from Bangladesh

As I was saying in Part I of this extremely short series of posts about Our Golden Hour, on Sunday morning I met with Maung Nyeu (the founder of this wonderful non-profit) at Algiers Cafe on Brattle Street in Cambridge. I handed over the materials created by some of my students in the Champlain College class I teach called Publishing in the 21st Century; what he gave me blew me away.

Over the summer (remember summer?) I had the idea of making room numbers to mount of the doors of the classrooms in the schools created and supported by Our Golden Hour.

Here’s the thinking. The children of the Chittagong Hill Tracts speak a variety of languages, but Bangladesh has a policy that the only way to be a Bangladeshi is to speak Bangla. Plenty of evidence, especially first-hand evidence in the Hill Tracts, shows that if you educate a minority child in an unfamiliar majority language, you’re condemning him or her to a miserable, unsuccessful education and an even more marginal life thereafter. But how to give the endangered Hill Tracts languages (and in some cases their endangered alphabets) a respect and status equal to the national language of Bangla?

That question is at the heart of much of the pedagogical thinking Maung is developing in the PhD program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education; my part is much more modest. I decided to start with the number on the classroom doors.

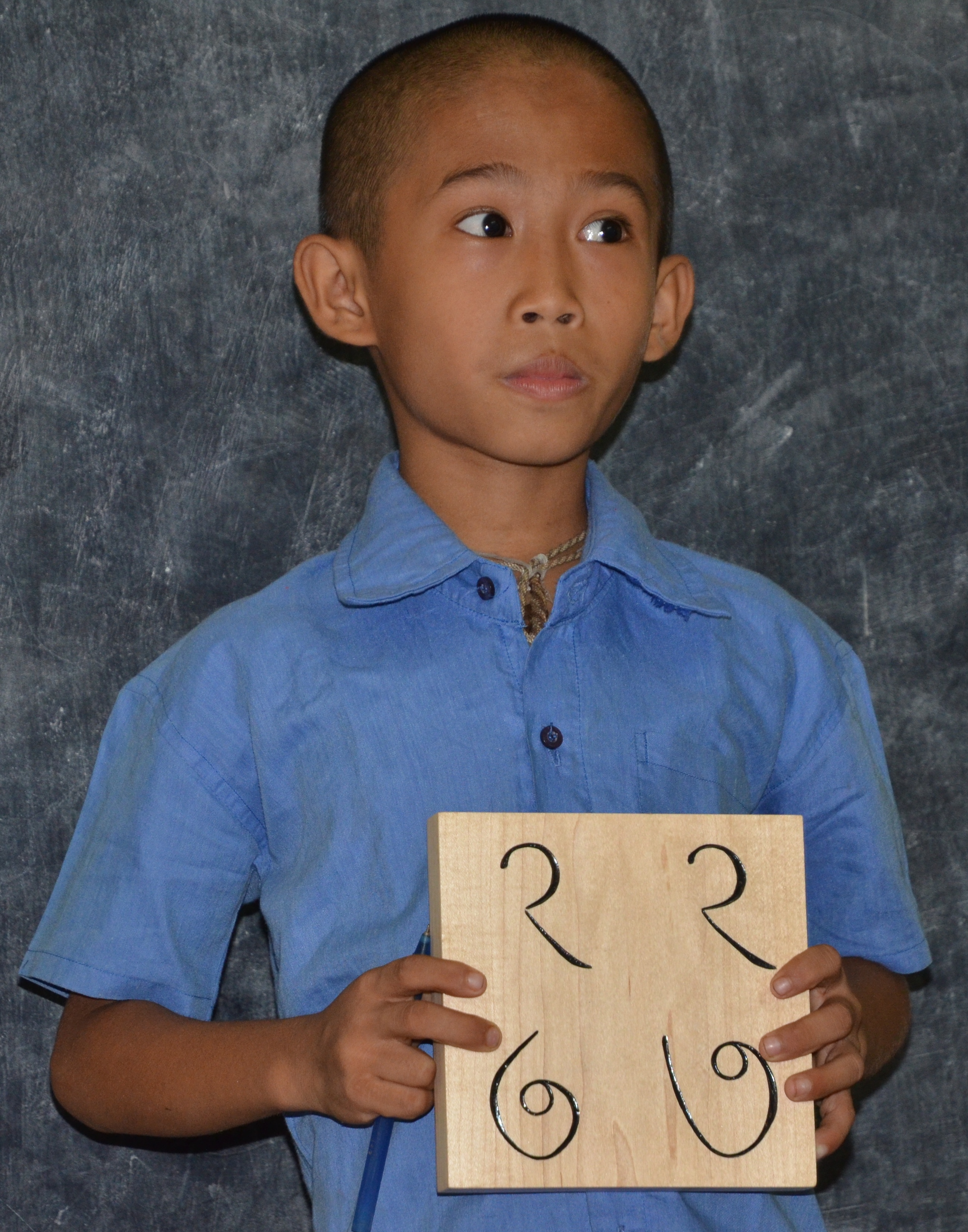

At the moment, each school teaches eight grades, though the numbers drop off alarmingly grade by grade as a variety of forces outside the schools combine to deter children from continuing their education. I decided to carve a plague to go on the door of each classroom with the room number (1 for Grade 1, 2 for Grade 2, and so on) in all four of the scripts/writing systems used in the Hill Tracts: Bangla, Mro, Marma, and Chakma.

Signage, you see, is very important. It gives authority and value to whatever it conveys, and in this case the number of the room is less important than the fact that the number is in the indigenous scripts, which are rarely if ever used for official signage in Bangladesh. The majority of Bangladeshis have never seen anything written or printed in Mro, Marma or Chakma–nor have the Mro, Marma or Chakma people themselves, reinforcing the sense that they are outsiders, even inferior outsiders. Hence the door numbers.

Another aspect was that I wanted all four letterforms to have equal value on the signs. It gives one wrong message to make the Bangla form bigger–but it gives a different wrong message to make it smaller and ignore the fact that these students will almost certainly need Bangla as part of their repertoire if they’re to make their way in the country at large. So the signs imply a kind of egalitarian diversity, or diverse equality.

So I made the signs, gave them to Maung, and pretty much forgot about them as he was lugging them halfway around the world. Until Sunday morning, when he gave me something wrapped in gold holiday gift wrap: a framed panel of photographs, each of one of his students recounting their family oral history story to their class–holding the door plaque corresponding to their grade.

It’s impossible not to be moved by these photos. In some the student is young and nervous. He or she may never have spoken in class before, let alone spoken to the entire class. In other the student is radiant with the joy of telling his or her story, in some cases in remarkable detail and at great length. One story, Maung told me, went on for 15 minutes. Whenever the kids in the classroom were included in the shot, they were looking on attentively and eagerly, for perhaps the first time in their educational lives.

Then there’s a sequence showing the brightest student in one of the older classes, a girl who is also the shyest student in the class. At first she is hesitant, looking down, holding her door number low. With each shot she gathers her courage; by the last she is speaking out. She has found her story, and her voice.

It was hard to believe I had made those pieces of wood the students were holding. It was astounding to be a tiny part of the transformation that was taking place.

It’s no exaggeration to say that even the smallest donation to Maung’s project makes a substantial difference to the lives of the 265 children at the three schools he helped to create. Read more about it HERE.

From now on, 20% of the profits from any Endangered Alphabets product will be donated to Our Golden Hour. See what I’m talking about on Etsy or Society6. Thanks.