Lessons from Ottawa, Part One

Between October 2-4, a group of some of the world’s top experts on indigenous languages met in Ottawa under the auspices of the Foundation for Endangered Languages.

Some of the research presented at the conference is of direct and urgent relevance to the Chittagong Hill Tracts Project, a collaboration of the Endangered Alphabets and the Champlain College Publishing Initiative. (The Endangered Alphabets Project is proactively interested in trying to reverse loss of indigenous language and culture; the Champlain College Publishing Initiative is helping to publish materials for indigenous language education.)

In particular the research presented in Ottawa addresses the benefits of trying to revive endangered indigenous languages, especially among children—very much what we’re trying to help achieve in Bangladesh.

I’m going to present a digest of this information in a short series of short posts. Even though much of the material is drawn from research in Canada, it applies to the efforts to support indigenous people’s education in Bangladesh, in the United States, and indeed all over the world.

I strongly invite you to repost them, tweet about them, or print them out, roll them up and tie them to the leg of a pigeon—anything to get the word out about the importance of this endeavor.

I’m very grateful to the FEL for inviting me and the Alphabets to Ottawa. I’m especially grateful for extended conversations with Carol Genetti, DJ Hatfield, Tom Saunders, Joan Argenter, Chris Moseley, John Clifton, and Nina Doré.

One of the issues facing the Chittagong Hill Tracts activities of the Endangered Alphabets Project is the question “How do you go about teaching indigenous people their own alphabet?”

The students of the Champlain College Publishing Initiative spent some time pondering this question and coming up with creative ideas, but let’s face it, we’re not experts in language instruction, nor in working with indigenous children.

Imagine my surprise and delight, then, when one of the first presentations I saw in Ottawa was by the renowned Christine Schreyer of the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus, who had actually worked with an indigenous community in Papua New Guinea (PNG) to create an alphabet for their language, no less.

Her challenge was a little different to ours, but no less formidable. Six villages along the shoreline of the Huon Gulf in Morobe Province, PNG, speak the Kala language. They are fairly remote: in most cases one travels from one to another by boat. And the rapid change of language in PNG meant that the six communities (totalling some 2,000 people) speak no fewer than four dialects.

Why bother with such a small population and its language? Because Schreyer’s collaborator John Wagner had realized, as is the case with most if not all indigenous languages, “how fundamental the [Kala language] was to the transmission of entirely basic, never mind more esoteric, levels of ecological knowledge and related skills.”

It has been said that every person is a library, and especially in the case of endangered languages, when one person dies a library is lost. Conversely, each language is a library of that culture’s collective experience and wisdom. To lose a language is to lose a dozen libraries.

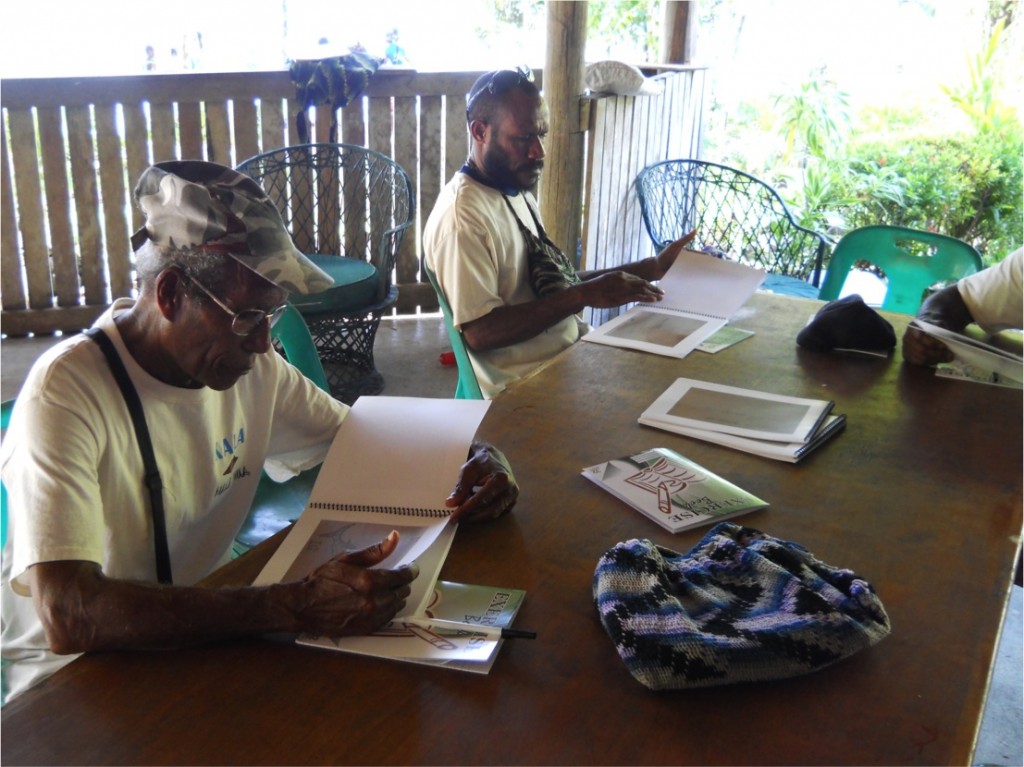

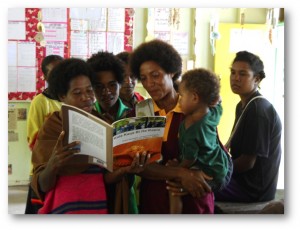

Rather than the specifics of the Kala language, I was interested in how Schreyer taught an alphabet to people some of whom, as she said in Ottawa, “had never held a pen.” The Kala Language Committee held workshops in each Kala village where Schreyer led the group in associating sound to symbol, making special note of uniquely Kala letters such as “a-titi” (which means the letter a with a wave symbol on top). After reviewing the letters, the participants would put their new knowledge into book making.

She worked with the community to discuss its collective book-making priorities. Together they came up with the following sequence of priorities:

· dictionary

· storybooks

· traditional mythological stories

· traditional historical stories

· local recent history and place names map

· stories about World War II, an important feature of Kala history

· song books

· books about local animals

· books about local plant and gardening practices.

In addition, Schreyer created an alphabet song, writing games, and book-making activities.

There was much more fine detail to the Kala experience, and many wonderful stories, especially about the collective experience of reading the dictionary together.

For my purposes, though, I had heard enough to be going on with. Back in Vermont, I’m about to gather the student gang and pore over Schreyer’s agenda–which, of course, the people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts may want to revise. But the picture is clearer, and the endeavor a little less daunting.