It’s All About Light

If I’d had any kind of artistic training, of course, I would have learned this truth back in tenth grade, I suppose. Instead, I’m learning it now, and learning it literally from every angle: it’s all about light.

When I’ve already carved the text, I have to have low light falling across the wood so I can see the exact edge of the cut letter, and paint right up to that edge. If the light is from the wrong angle or the wrong direction, it’s literally impossible to tell where to paint.

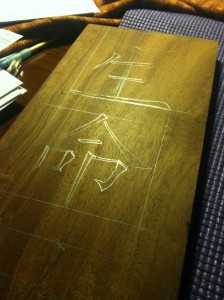

Before that, at the carving stage, I have to be able to see the light reflecting off the pencil mark or carbon paper image.

This is at its most difficult when for reasons of my particular ambition at the time, I’m trying to create a text that is both (a) on a dark wood, and (b) is drawn freehand in pencil. I love drawing Chinese characters freehand: you get a wonderful sense of the sweep of the brush, as if in the turn of your own wrist you feel the very origin of the stroke itself, the entire history of writing.

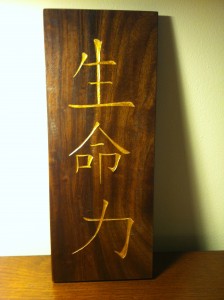

In the particular case, I was using the very last few inches of the incredible wood nobody can identify, the kind I call marblewood because it is so hard, so striated, so dense and heavy. That single narrow board that was unearthed from the warehouse out behind Sterling Hardwoods has yielded four carvings, all of them extraordinary, all now in different corners of the country, each priceless in its own way.

On this one I wanted to create the Chinese characters for “life force.” To do so, and to do so freehand, I had to pay attention, above all, to light.

As you can sort of tell from the photograph at the top of this column, I had to map out the wood in pencil squares, then draw each stroke, turning the wood this way and that to be able to see the reflection of what I was doing. It was very odd: because the pencil-lead itself was never visible, only the lamplight glinting off its metallic particles, in a way it felt as though I were not drawing with graphite but with light itself.

In the end it all came out quite well, I think, and yet again it was all about light: because the wood was so dark I used gold paint, and again what you see is not really the paint, the liquid content of which was immediately absorbed into the wood. It’s the metallic flakes, and bouncing off them and yet being transformed by them, the light itself.

January 6, 2013 @ 8:09 pm

I thought that you did a credible job incorporating comments about light and your work. All that I can possibly add is that the “angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection” not unlike a pool ball banking off a cushion. In other words, light goes goes in and comes out at the same angle. So when you carve a curved concavity, light will bounce out at subtle angles that will create the gradations of shading that signal the eye to see a curved surface where the applied color is uniform. This quality is what the carver or sculptor brings to the process. As opposed to the Chinese calligrapher that brushes ink upon a flat surface, you are introducing a very real (albeit shallow) “z” axis or third dimension to the letter forms, making them sculptural in addition to everything else. A point worth mentioning, I should think.

Bob Selby