The Endangered Alphabets’ European Tour, Part II: Even Before We Left Boston

The Alphabets Lite edition in its London bus-themed wheely-case left Vermont last Sunday, June 24th. The plan was to take a couple of days in Boston so my daughter Maddy could visit some prospective colleges and art schools, and then the Alphas and I’d take off from Logan Airport on the evening of Wednesday 27th.

The Alphabets couldn’t wait, though, and even before I left a remarkable chance meeting took place that may define my next direction in this unfolding project.

As it happened, Maddy was no longer interested in the college we were scheduled to visit on Tuesday 26th, so we had, in effect, a day off. We drove across the river to Cambridge, where Maddy and her mother went shopping and I met someone from the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh.

I don’t think I’m going to reveal his actual name just yet, because his family back in Bangladesh may face retaliation from the government, but the story he told is familiar and well documented. Let’s call him Sri.

Sri is from the Marma Indigenous community of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), a remote south-eastern corner of Bangladesh. Thirteen indigenous groups call this mountainous region home–or they would do if the Army were not involved in a steady program of ethnic cleansing. Sri’s village was burned down by the Army when he was a small child, and his family became internally displaced, forced to move on time and again. On the infrequent occasions when he was able to attend school, he couldn’t understand the teacher, who spoke in Bangla, the official national language. This was regarded as a sign of stupidity or inattention, and he was frequently caned or beaten.

Eventually his mother homeschooled him–to such good effect that he became the first of his people to be educated in the United States. He got a degree in engineering from Harvard, and went back to the CHT to build a school for the children of his people.

The building in itself, though, he came to realize, was only part of the solution–so he went back to Harvard to do a graduate degree in education.

“The Bangladesh government gives us no constitutional recognition as indigenous people,” he has written. “As a result, our children are disadvantaged by an education system that does not recognize our language or culture. In Bangladesh, the education curriculum is rigidly centralized and follows a single national curriculum in Bangla only, the majority language. Most CHT children do not speak Bangla at home. As a result, they struggle to understand the language of instruction.

“Moreover, the content is often culturally inappropriate for them. This situation sets up CHT children for failure, leading to the high dropout rate. More importantly, in many communities, we have only few elders alive today who can read and write in our scripts. These are the few last remaining people on earth with the knowledge to read and write in our scripts. Our languages are on the brink of extinction.

“So, we started a non profit and CHT Oral History Project, an initiative to preserve the local language and culture of CHT people by publishing children’s books based on oral history passed down through generations.”

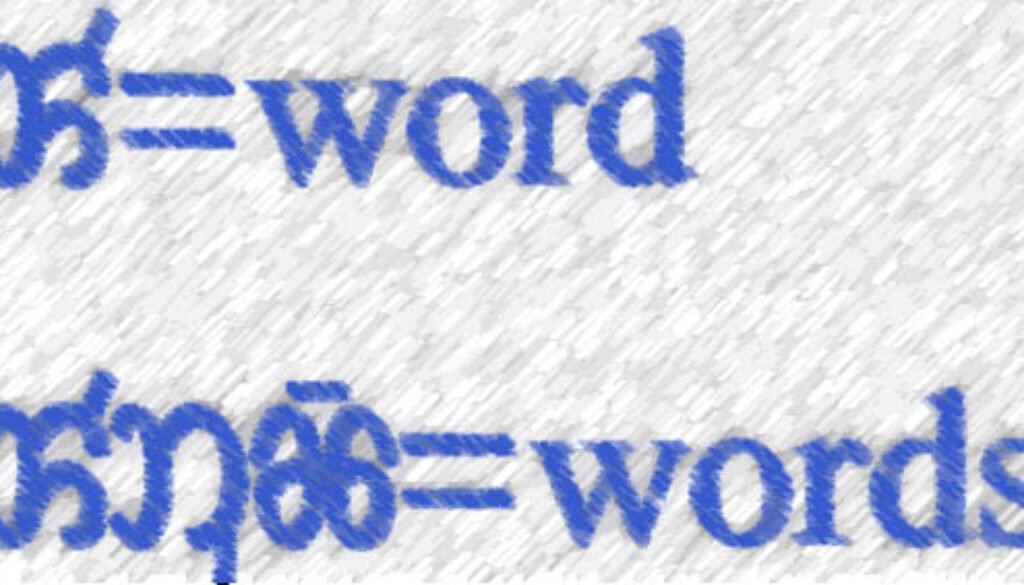

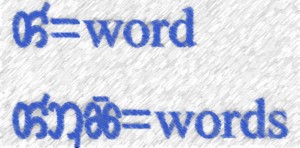

Publishing children’s books in Mro, Marma and Chakma, that is, which are not only different languages to Bangla but have their own scripts. How can children read their own history, he asked me, if they don’t understand the script in which it was written? Especially when the teacher and the government are giving them the same kind of account of their own history as Midwest teachers and the US government gave the Cherokee for a century or more?

What’s more, this is the kind of project that would be all too easy for the Bangladesh government to discredit or destroy. So there and then I decided to partner with Sri, and over the next few days we pulled in more partners: a linguistic anthropologist from Yale, a typographer from Cambridge (England), and a calligrapher from the Rhode Island School of Design, now working in Barcelona. The theory is that with those big names (especially those big Western names) behind him, it’ll be that much less likely he’ll be shut down or arrested.

So we have two principal aims, and one sub-aim. One is to help him create a calligraphic digital typeface that is authentic to the writing traditions of his people, so he can then use his educational theory to create pedagogically valid schoolbooks for the kids in the school. (Oh, and he plans to add another floor to the school. Yu just can’t stop these teacher-engineers.)

The second is to hold a series of informational talks and meetings, starting in Harvard, to rally contacts and support, so when he speaks, he speaks with the voice of many.

The sub-aim is my own small part in this. One of the interesting things about signage is that it conveys authority. My goal is to create a series of signs in Marma, Mro, and Chakma for display in the CHT so for the first time in decades, the indigenous peoples of the Hill Tracts will see strong, authoritative statements in permanent material prominently displayed in their own communities.

I may also do a fundraising campaign on IndieGoGo or Kickstarter to try to raise money to print the books and fund the signage. Please feel free to comment on this page to make suggestions or offer support.

Tim

P.S. Next time I promise to talk about what happened when the Alphabets actually reached Europe.

Endangered Alphabets » Blog Archive » The Endangered Alphabets’ European Tour, Part III: Cambridge University

July 8, 2012 @ 10:01 pm

[…] the projected collaboration with members of the indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (see Episode II of this saga), he was all over it, recognizing at once the need to create a digital typographical expression of […]