Our Golden Hour Part I: Gifts for Bangladesh

Quite quietly, in the upper room of Algiers Cafe on Brattle Street in Cambridge, an extraordinary seasonal gift exchange took place yesterday morning.

Quite quietly, in the upper room of Algiers Cafe on Brattle Street in Cambridge, an extraordinary seasonal gift exchange took place yesterday morning.

I was meeting with my friend, colleague, and collaborator Maung Nyeu, founder of the amazing non-profit organization Our Golden Hour, which aims to provide mother-tongue education for indigenous children in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh. With us was Kim Wilson, a microfinance expert who teaches at the Fletcher graduate school of business at nearby Tufts University.

The gifts I was carrying for Maung were created mostly by three students–Paige Merrow, Rhianna Graham-Frock, Alex Warlick–in my Publishing in the 21st Century class at Champlain College in Burlington. With a suitably festive air, I passed the presents over the table to Maung one by one.

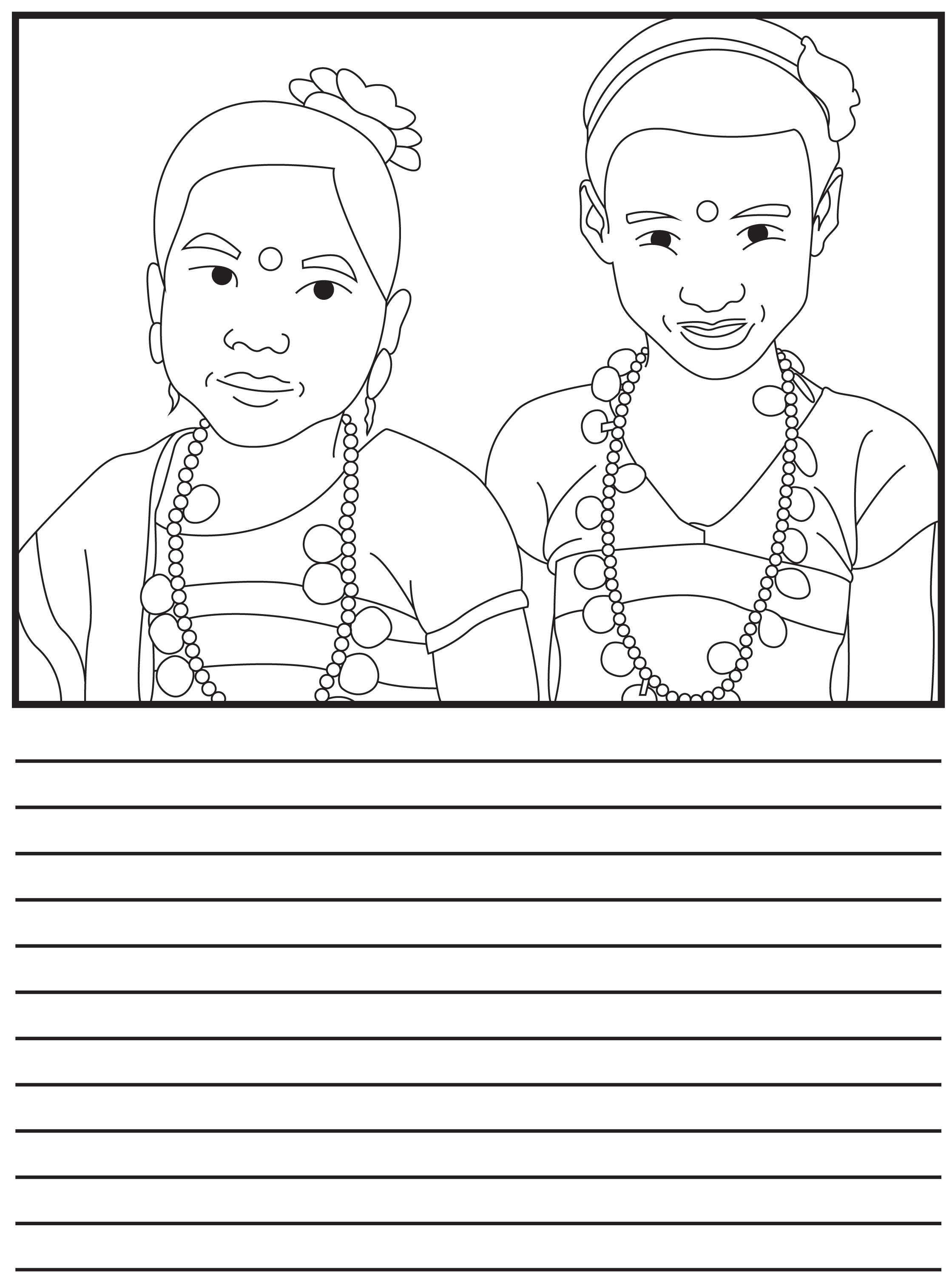

The first was our coloring book, Color My Story. One of the pages is reproduced over there on the left.

Here’s the thinking. We wanted to create something interactive, partly because kids are more engaged in learning if it involved action and materials they create themselves, but also because the education in Bangladesh, as in much of the developing world, is anything but kid-centric: the teacher dominates the classroom and, as Maung said, the children are often afraid even to lift their eyes to look at him, let alone express opinions or be creative.

We also wanted to create something non-grade-specific, as these schools have very, very, very, very few resources, and if a coloring book or coloring sheets could work in different ways for different grades, so much the better. (Thinking along the same lines, we threw in colored pencils as the school will not have such items, and two pencil sharpeners, ditto. The money for all this came from a Kickstarter my students ran last semester, by the way.)

So my students conceived of a coloring book, or a collection of coloring sheets, that could also be used for writing stories–hence the ruled lines under the picture. The Hill Tracts children can color the image and then add their own visual embellishments, and then write something about it, either from their own experience or from their own imagination. The facing page, by the way, is blank, to allow further drawing or writing.

The images were based on photos Maung sent us. Another Champlain student, Jane Adams, did a spectacular job of rendering the photos into outline form, preserving their visual character and, just as importantly, the characteristic features of dress, landscape, people’s faces.

When Maung saw the coloring books, his face lit up and his mouth fell open. Then he explained why these apparently simple creations are something exceptional.

For a start, he said, the children in the Chittagong Hill Tracts who start working with these books in January will never have had an art class. The act of producing visual images on paper, something we see as essential both in the sense of its importance to a child’s development and in the sense of it being part of our essence, is not taught. The only books they will have seen are textbooks.

Next, he went on, these images are vital because they are familiar. This has at least two very important qualities, especially in the context of trying to save an endangered indigenous culture.

One, the children can color and write about what they know, which makes the act of creation more interesting, enjoyable, and easier. Maung tells the story of his own schooling, when he was forced to memorize Wordsworth’s poem “Daffodils,” even though neither he nor anyone he knew had ever seen a daffodil or knew what it looked like.

Two, the choice of images gives value to the child’s own background and experience. This is a major factor in minority education everywhere; here it is especially important because some of the images represent a cultural way of life that is different from what takes place elsewhere in Bangladesh, whose government denies indigenous peoples their civil rights and even denies the existence of any indigenous peoples in Bangladesh.

And from a pedagogical point of view, the coloring book fits in with a magnificent and novel (especially for the developing world) series of curricuar activities going on in the schools. The children are asked to go back to their villages and ask their grandparents to tell them a story they heard when they were little boys or girls. The children come back to school and retell these stories, and when they do so for once they are at the head of the class–and in telling the stories they often use gestures and expressions they have picked up from their elders. They get excited; the rest of the class listens, rapt. The storytelling is videotaped and the transcribed story is the ready for publication as a children’s book for the schools.

This cycle has all kinds of importance and value. Once again, it gives respect to the students’ own culture, and it also heals any potential generation gap by linking grandparent and grandchild. It preserves some of the mythology and folklore of the region–a region currently being overrun by armed settlers from elsewhere in Bangladesh who have been promised cheap or free land in the Hill Tracts–but that mythology and folklore itself preserves survival strategies, hard-earned wisdom, information about medicinal plants. It’s the education that matters to those people in that place as much as an education in literacy and numeracy.

The other gift from my students was a set of alphabet stamps.

We approached my friend Paul Ledak of Williston, who has a computer-operated laser, and Paul kindly agreed to take the 33 letters of the Marma alphabet and burn them in sheets of rubber. (Well, technically he burns the rubber around them so the letters stand out. The smell is appalling.)

The Publishing students then took the individual letters and stuck them on stamp blocks, inserted handles, and voila! Alphabet stamps for kids who don’t know their own (endangered) alphabet, or can’t yet form letters.

I handed Maung a cardboard box with the 66 stamps–two copies of the Marma alphabet. What he gave me in return left me speechless with delight. Read about it in the next post, “Our Golden Hour II: Gifts from Bangladesh.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that even the smallest donation to Maung’s project makes a substantial difference to the lives of the 265 children at the three schools he helped to create. Read more about it HERE.

From now on, 20% of the profits from any Endangered Alphabets product will be donated to Our Golden Hour. See what I’m talking about on Etsy or Society6. Thanks.

March 13, 2016 @ 11:21 am

Dear Sir, I am visit your activities. this activities is very fine. Ple sent your Bangladesh or CHT address.

Thanks.

Tuhin Chakma

chakmatuhin79@gmail.com

CHT.Rangamati.Bangladesh.

March 13, 2016 @ 11:27 am

Thanks for your comment! I’m afraid I don’t have a Bangladesh address. I live in the US.